T-Th 9:05 or 11:15

in Kimball B11

CS 1110: Introduction to Computing Using Python

Spring 2013

About:

Announcements

Staff

Consultants

Times & Places

Syllabus

Materials:

Texts

Python/Komodo

Command Shell

Terminology

Handouts:

Lectures

Assignments

Labs

Assessment:

Grading

Exams

Resources:

CMS

Piazza (link)

Piazza (about)

VideoNote

AEWs

FAQ

Python Library

Online Python Tutor

Style Guide

Academic Integrity

Authors of these pages: D. Gries, L. Lee, S. Marschner, & W. White, over the years

Assignment 7:

Breakout

Due to CMS by Saturday, May 4th at 11:59 pm

Authors: E. Roberts, D. Gries, L. Lee, S. Marschner, W. White.

Significant changes to printed handout marked in orange.

Sat Apr 28, 12:21:pm

(a) clarification regarding relationship between

setup and STATE_PAUSED; see sections

3,

4.2 and 4.3.

(b) Folded in some remarks from Piazza conversations:

use of keyword arguments;

don't set the velocity too large.

Mon Apr 29, 10:20am: Folded in remarks from Piazza about using keyword arguments in subclasses

to 4.2.

Your task is to write the classic arcade game Breakout.

If you have never played Breakout before, there are lots of versions online, particularly as flash games. The old school versions give you an example of the basic gameplay, though they are considered boring by modern standards. Most of the modern versions of Breakout were inspired by the Arkanoid series and have power-ups, lasers, and all sorts of weird features. The flash game Star Ball is an example of a fairly elaborate Breakout variant.

One of the main challenges with this assignment is that the scope of it is completely up to you. There is a bare minimum of functionality that you must implement; you must have all the features of an old-school Breakout game. But after that point, you are free (and encouraged) to add more interesting features to your game. The video to the right shows a solution with several extra features such as sound and a countdown timer. You should not feel compelled to add these features to your game. You are permitted to do anything that you want, provided that the basic functionality is there.

This assignment is easily within your grasp, but it is more open-ended than the previous assignments and takes some planning to finish efficiently. Our basic solution is 300 lines longer than the skeleton; the fancier solution in the video above is about 500 lines and has 11 helper methods beyond those in the original code skeleton. You just have to start early, break the problem up into manageable pieces, and program and test incrementally. Below, we recommend a sequence of implementation stages that works well for many students, and give suggestions for staying on top of the project. If you follow our advice and test each piece thoroughly before proceeding to the next, you should be successful.

Learning Objectives

This final assignment has several important objectives.

- It gives you experience with event-driven program organization.

- It gives you experience with programming animation and simple physics.

- It gives you experience with an open-ended project that is not fully specified.

- The end result is fun to play with!

Table of Contents

- Before You Get Started

- Breakout

- The Basic Game

- Create a Welcome Screen [suggested by Apr 26]

- Set up the Bricks [suggested by Apr 27]

- Create (and Animate) the Paddle [suggested by Apr 29]

- Create a Ball and Make it Bounce [suggested by Apr 30]

- Check for Collisions [suggested by May 2]

- Finish the Game [due on May 4th]

- Extending the Game

- Completing the Assignment

Before You Get Started

Academic Integrity

This assignment is similar to one given in previous offerings of CS1110. It is a violation of the Code of Academic Integrity for you to be in possession of or to look at code (in any format) for this assignment of anyone in this class. This includes older versions of this assignment from back when this course was taught using Java (even though the solution is different, the ideas are similar).

You should also not show another student your program (this includes publicly posting your code on Piazza). Please do not violate the Code; penalties for this will be severe. We will try hard to give you all the help you need for this assignment.

Collaboration Policy

You may do this assignment with one other person. If you are going to work together, then form your group on CMS as soon as possible. If you do this assignment with another person, you must work together. It is against the rules for one person to do some programming on this assignment without the other person sitting nearby and helping.

With the exception of your CMS-registered partner, you may not look at anyone else's code or show your code to anyone else, in any form what-so-ever.

Assignment Source Code

The first thing to do in this assignment is to download the zip file A7.zip from this link. You should unzip it and put the contents in a new directory. This zip file contains the following:

controller.py-

This file contains the controller class (

Breakout) for this application. This is the only file that you need to modify for this assignment. However, note that it has no application code. __main__.py- This module contains the application code for this assignment. It is the module you run from the command line.

graphics.py- This is a module with the graphics object classes that you will use for drawing in the game window. You should not modify this file. See the online documentation for how to use these classes.

graphics.kv-

This is the Kivy file associated with

graphics.py. Do not modify this file. Sounds- This folder is a list of sound effects that you may wish to use as part of your extensions. You are also free to add more if you wish; just put them in this folder. All sounds must be WAV or OGG files, recorded at 16 bits and sampled at 44.1 kHz (i.e. CD quality).

Fonts- This folder is a collection of TrueType Fonts, should you get tired of the default Kivy font. You can put whatever font you want in this folder, provided it is a .ttf file. Other font formats (such as .ttc, .otf, or .dfont) are not supported.

Images-

This folder is a collection of images that you may wish to use as

part of your extensions. The

class

GImageallows you to animate images in this game, should you wish. You can also use them to provide a background (if you add the image to the window first).

To run the application, put all of this in a folder, and give

the folder a name like breakout. Because of the

module __main__.py, to run this program you should

change the directory in your command shell to just outside

of the folder breakout and type

python breakout

__main__.py.

You will only modify the controller module described above. The class

Breakout is a subclass of the class GameController.

As part of this assignment, you are expected to read the

online documentation which describes how

to use the basic classes.

Assignment Scope

As you can see from the online documentation,

the class Breakout needs to implement five main methods.

They are as follows:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

initialize() |

Initializes the game state. Because of how Kivy works, initialization code should go here and not in the initializer (which is called before the window is sized properly). |

update(dt) |

Update the graphics objects for the next animation frame. Called

approximately 60 times per a second; dt is the time since

the last call.

|

on_touch_down(view,touch) |

Called when the user presses the mouse button or touches the screen,

immediately following the event (while the button is still down or

the finger is still on the screen). The parameter touch

holds information about the touch event, in particular the position

in the window, given by the attributes x and

y.

|

on_touch_up(view,touch) |

Called when the user releases the mouse button or removes their finger

from the screen.

The parameter touch holds information

about the touch event.

|

on_touch_move(view,touch) |

Called when the user moves the mouse while the button is down, or

moves their finger while it is touching the screen.

The parameter touch holds information

about the touch event.

|

Obviously, you are not going to put all of your code in those five methods; the result would be an unreadable mess. An important part of this assignment is developing new methods whenever you need them, in order to keep each method small and manageable. Your grade will depend partly on the design of your program. As one guideline, points will be deducted for methods that are more than 50 lines long (including the specification).

You may also need to create new classes (see the example for the ball object), or add new variables to existing classes. When you add a new variable, you must state its invariant, and your code must maintain the invariant.

As an example, you will notice that we have already provided you

with several example instance variables in Breakout, together

with comments that specify the invariants. These fields

and invariants are good ones to use, but the design of this program

is up to you, and if you prefer to do things differently, you may.

However, we expect you to ensure that each of the five methods maintain the

invariants: they should be true before and after each method call. If you

have an alternate design that does not follow our invariants, this is OK, but

you must change the

invariants so that they are maintained by your code.

If you show your code to an instructor, TA, or consultant and they see a method with no specification or a field without an invariant, they will ask you to go away, fix it, and come back at another time.

Pacing Yourself

You should start as soon as possible. If you wait until the day before this assignment is due, you will have a hard time completing it. If you do one part of it every 2-3 days, you will enjoy it and get it done on time. Below we propose a schedule that you can follow to comfortably finish the program, but if you want time to add optional extensions, you'll need to step up the pace of the basic implementation a bit.

Implement the program in stages, as described in this handout. Make sure that each stage is working before moving on to the next stage. Do not try to get everything working all at once, and do not continue with the next phase before you are sure the previous phase is correct. Even experienced programmers like your instructors would not try to write this much code without testing it in stages, because we know from hard experience that it will waste time to do so. Above all, do not try to extend the program until you get the basic functionality working. If you add extensions too early, debugging may get very difficult.

Getting Help

We have tried to give you as much guidance in this document as we can. However, if you are still lost, please see someone immediately. The individual bits of code needed for this assignment are all simple, but it is a fairly involved and open-ended project compared to the earlier ones, and it requires more time spent figuring out how to organize the program. Get started early! Get help early and often by talking to the course instructors, TAs, or consultants. See the staff page for more information.

In addition, you should always check Piazza for student questions as the assignment progresses. We may also periodically post announcements regarding this assignment on Piazza and the course website.

Breakout

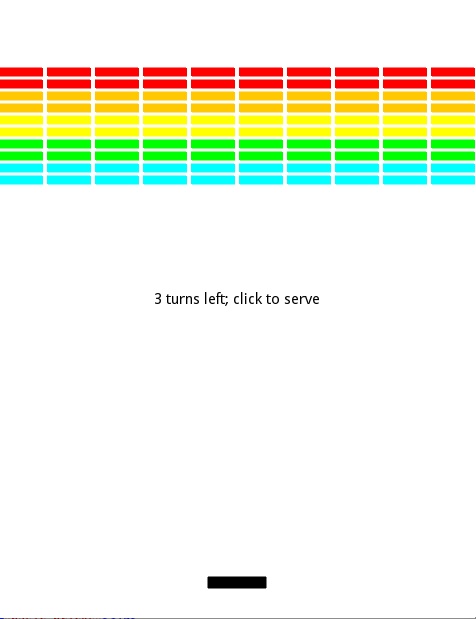

The initial configuration of the game Breakout (after the user has clicked past the welcome screen but before they have clicked to serve the ball) is shown in the left-most picture below. The colored rectangles in the top part of the screen are bricks, and the slightly larger rectangle at the bottom is the paddle. The paddle is in a fixed position in the vertical dimension; it moves back and forth horizontally across the screen along with the mouse (or finger, on a touch-screen device)—unless the mouse goes past the edge of the window.

Starting Position |

Hitting a Brick |

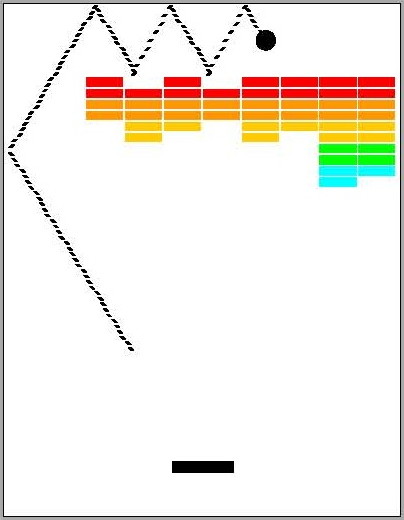

A complete game consists of three turns. On each turn, a ball is launched from the center of the window toward the bottom of the screen at a random angle. The ball bounces off the paddle and the walls of the world, in accordance with the physical principle generally expressed as "the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection" (it is easy to implement). The start of a possible trajectory, bouncing off the paddle and then off the right wall, is shown to the right. The dotted line is there only to show the ball's path and will not actually appear on the screen.

In the second diagram above, the ball is about to collide with a brick on the bottom row. When that happens, the ball bounces just as it does on any other collision, but the brick disappears. The left-most diagram below shows the game after that collision and after the player has moved the paddle to put it in line with the oncoming ball.

Intercepting the Ball |

Breaking Out |

The play on a turn continues in this way until one of two conditions occurs:

-

The ball hits the lower wall, which means that the player missed it with the paddle.

In this case, the turn ends. If the player has a turn left, the next ball is served;

otherwise, the game ends in a loss.

- The last brick is eliminated. In this case the player wins, and the game ends.

Clearing all the bricks in a particular column opens a path to the top wall. When this delightful situation occurs, the ball may bounce back and forth several times between the top wall and the upper line of bricks without the user having to worry about hitting the ball with the paddle. This condition, a reward for "breaking out", gives meaning to the name of the game. The last diagram above shows the situation shortly after the first ball has broken through the wall. The ball goes on to clear several more bricks before it comes back down the open channel.

Breaking out is an exciting part of the game, but you do not have to do anything in your program to make it happen. The game is operating by the same rules it always applies: bouncing off walls, clearing bricks, and obeying the "laws of physics".

Game State

One of the challenges with making an application like this is keeping track of the game state. In the description above, we can identity four distinct phases of Breakout.

- Before the game starts, when the bricks are not yet set up

- While the game is ongoing, but the player is waiting for a new ball

- While the game is ongoing, and the ball is in play

- After the game is over, when the player has won or lost

Keeping these phases straight are an important part of implementing the game.

You have to reason carefully about how these states lead to one another to implement

on_touch_down and update correctly. For

example, if the game is ongoing, and the ball is in play, the method on_touch_down

is used to move the paddle. However, if the game has not started yet, the method

on_touch_down should set up the bricks and start a new game.

For your convenience, we have provided you with constants for four states.

STATE_INACTIVE, before the game has startedSTATE_PAUSED, when the player is waiting for a new ballSTATE_ACTIVE, when the game is ongoing and ball is in playSTATE_COMPLETE, when the game is over (won or lost)

The current state of the application is stored in instance variable _state.

You are free to add more states when you work on your game extensions.

However, your basic game should stick to these four states.

While the design of your program is up to you, it is a good idea to follow the rule that the game state is only changed or examined in the five main methods. This keeps the logic about state sequencing all in one place where you can think about it together. You should move almost all the other code into helper methods, but if many helper methods fiddle with the state it can rapidly become difficult to reason about what happens when.

The Basic Game

We have divided these instructions into two parts. The first part covers the game features that you are required to implement. Once you do that, you can add extensions if you like (though you will not lose any points if you do not have extensions; they are optional, and a perfect implementation of the basic game receives a maximum score).

Create a Welcome Screen

We start with a simple warm up to get used to adding and removing graphics elements. When the user starts up the application, they should be greeted by a welcome screen. (If you add extensions, you can embellish your welcome screen to be as fancy as you wish. But for now, keep it simple.)

Your initial welcome screen should display a text message like the one shown to the right. It does not need to say "Press to Play". It could say something else, as long as it is clear that the user needs to click the mouse (or press the screen) to continue. You also do not have to use the dreaded Comic Sans font like we have.

To create a text message, you need to create a GLabel

object and add it to the view. Since the Breakout class is a subclass of

GameController, it inherits an attribute called view

which is an instance of GameView.

Objects of class GameView

have a method called add, which allows you to add graphics objects;

as is described in the documentation, the view draws graphics objects "bottom up"

using the order they were added to the view (so graphics objects added later are

drawn on top).

As you can see from the documentation for GLabel

and GObject,

graphics objects have a lot of attributes to specify things such as position, size,

color, font style, and the like.

You can set some or all of them by specifying them as keyword arguments to the initializer;

this means you can write things like GLabel(text="hi", font_size=12, font_name="Times.ttf").

You do not have to assign all of these attributes

before you add the label to the view. If you change them after adding the GObject or GLabel to the

view, then the view will alter its display of the graphics object

at the next animation frame. You should experiment with these attributes

to get the welcome screen that you want. Remember that screen coordinates in

Kivy start from the bottom-left corner of the window.

Since the welcome message should appear as soon as you start the game, it belongs

in the method initialize that is one of the first important methods

of the class Breakout. Put your code there and try running the application.

Does your welcome message show up?

Initializing Game State

Another thing that you have to do in the beginning is initialize the game state. The

instance variable _state should start out as STATE_INACTIVE. That way

we know that the game is not ongoing, and that the program should not (yet) be attempting

to animate anything on the screen. We have initialized _state inside of

the method initialize for you.

Dismissing the Welcome Screen

The welcome screen should not show up forever. The player should be able to dismiss

the welcome screen (and start a new game) when he or she clicks the mouse or

touches the screen. When this event happens, the application will call your

function on_touch_down.

This means that you should add code to on_touch_down that removes

the message in your welcome screen. In addition, the function should change

the game state from STATE_INACTIVE to STATE_PAUSED,

indicating that the game has now started (but there is no ball yet). You are

not ready to actually write the code for the game, but switching states is

an important first activity.

In implementing on_touch_down, you need to write the body so

that it only removes the message if the state is currently STATE_INACTIVE.

The method on_touch_down is called whenever the application receives

mouse or touch input. While you are currently writing this function to make it remove the welcome

message, you will use the method for other things in the future (like move the paddle).

You do not want your Breakout application trying to remove a message that is not there.

Hence, you now have your first example of a non-trivial invariant in Breakout:

If the state isYou might as well add this to the documentation for constantSTATE_INACTIVE, there is a welcome message in the view; if the state is notSTATE_INACTIVE, there is no welcome message in the view.

STATE_INACTIVE.

Now try out the application. If it is working correctly, you should start up with a welcome message and then get a blank screen when you click the mouse. If you click again, your program should not attempt to remove the message again.

Important Considerations

This first part of the assignment looks relatively straightforward, but it

gets you used to having to deal with controller state. In this part, you already immediately

have to add attributes beyond the ones that we have provided.

In particular, to remove a graphics object from the view, you have to create have a variable

that stores the graphics object you wish to remove (in this case, our GLabel

object). If you put the GLabel object that you created in

initialize in a local variable, that variable is lost after

initialize finishes, and other methods cannot remove the message.

You must put the GLabel object

in an instance variable so that on_touch_down can instruct the view to remove it.

Our example code creates an instance variable _message that is intended for

this purpose.

As you progress through this assignment, you will find yourself adding more and

more variables to your Breakout instance. Every time you need to remember

some result for later use by another method, you need to use an instance variable to

store that information.

The challenge is to add enough variables to get the work done without having too

many of them. Remember, in Python it is easy to create instance variables willy-nilly

and thereby confuse yourself and your grader. Please follow the conventions we have been

advocating: only create instance variables in the initializer, and document all instance

variables in the class invariant (in the docstring for the class). Make sure to include

an appropriate (both useful and truthful) invariant

for each variable; style points will be deducted if you create undocumented variables.

Try to finish this part by April 26 (i.e. two days after starting the assignment). You will spend most of your time reading the online documentation. But this will give you a solid understanding of how this application works.

Set up the Bricks

Once the game has started, the first step is to put the various pieces on the playing

board. Despite the name, you should not do this in

Once the game has started, the first step is to put the various pieces on the playing

board. Despite the name, you should not do this in initialize.

That method is for things that happen before the game has started (like the welcome screen).

You do not place the bricks until you start the game

the user clicks to remove the welcome screen, which is when the state

changes to STATE_PAUSED.

Because that state change

happens in on_touch_down, this is a good

place to put your code to set up the bricks. However, you will quickly discover

that on_touch_down gets very complex, because it has to do

a lot of things. Therefore, the best option is to create a helper method (with

a name of your choosing) that sets up the bricks, and call that helper method

in on_touch_down. The helper should be called

just after when you

set the state to STATE_PAUSED

, which you did in the previous task.

Please place this and all other helper functions that you write after the comment

starting "ADD MORE HELPER METHODS", to make it easier for

the graders (and you) to find them. Be sure to specify all helper functions clearly with

a docstring; style points will be deducted otherwise. We also recommend that your

helper methods be hidden (start with an underscore). You are free to use either

camelCase or underscores in naming your methods, but we ask that you be consistent.

The helper function should set up the bricks as shown.

The number, dimensions, and spacing of the bricks, as well as the distance from the

top of the window to the first line of bricks, are specified using global constants

given in module controller. The only value you need to compute is the

x coordinate of the first column, which should be chosen so that the bricks

are centered in the window, with the leftover space divided equally on the left and

right sides

The colors of the bricks remain constant for two rows

and run in the following sequence: RED, ORANGE, YELLOW,

GREEN, CYAN. If there are more than 10 rows, you are to start

over with RED, and do the sequence again. We suggest that you add a constant BRICK_COLORS

to your module that lists these colors in an appropriate way to help with this.

All objects placed on the playing board are instances of subclasses of the class

GObject. For example, bricks and the

paddle are objects of subclass GRectangle.

To define a rectangle, use the attributes pos, size, linecolor, and fillcolor to specify how it looks on screen.

You can either assign the attributes after the object is created, or assign them in

the constructor using keywords; see the online documentation for more. When you

color a brick, you should set that color so that its outline is the same color as

the interior (instead of black).

There are some advantages to making a subclass of GRectangle to represent bricks;

you can offload some of the setup (e.g. setting the color and size) to your brick class,

and you can distinguish the bricks from other GRectangle objects using

isinstance. However, this design decision is up to you; you may prefer just

to instantiate GRectangle directly.

If you want your subclass's initializer to be able to take keyword arguments

and pass them to the superclass's __init__ function, have **kw be one

of the “parameters” (you can use whatever parameter name you like,

but you have to have the double-asterisks to unpack the input) to your

__init__ function, and then when you call the superclass's __init__, have **kw

be an argument.

To begin, you might want to create a single Brick object of some position

and size and add it to the playing board, just to see what happens. Then think about how

you can place the BRICK_ROWS (in this assignment, 10) rows of bricks.

You will probably need a loop of some kind. We do not care if it is a for-loop or a

while-loop; just get the job done.

Important Considerations

When you add a brick, it needs to be added in two places. It needs to be added to the

view, which draws it; it also needs to be added to a list in the controller, so

that you can remove it later (when the ball hits it). We have provided the hidden

instance variable _bricks for precisely this purpose. Note that _bricks

is a list and is intended to hold all of the bricks, not just one.

As a result, when you want to add a brick with name (stored in variable) brick,

you will need to use both of the following commands:

self.view.add(brick) # Add to view

self._bricks.append(brick) # Add to controller

self.view.remove(brick) # Remove from view

self._bricks.remove(brick) # Remove from controller

_bricks, then your ball will pass right through it. On the hand, if you

add it to _bricks but not to the view, you may get an invisible brick

that will block your ball (not yet, however, as you have not yet implemented collisions).

You should make sure that your creation of the rows of bricks works with any

number of rows and any number of bricks in each row (e.g. 1, 2, ..., 10, and perhaps more);

see the description of function fix_bricks below.

This is one of the things we will be testing when we run your program.

Try to finish this part by April 28. All you need to do is to produce the brick diagram shown above (after the welcome screen). Once you have done this, you should be an expert with graphics objects. This will give you considerable confidence that you can get the rest done.

The Function fix_bricks

When you are testing the program, you should play with just 3-4 bricks per row and 1-2 rows of bricks. This will save time and let you quickly see whether the program works correctly when the ball breaks out (gets to the top of the window). It will also allow you to test when someone wins or loses. If you play with the default number of bricks (10 rows and 10 bricks per row), then each game will take a long time to test.

Unfortunately, testing in this manner would seem to require changing the values of the

global constants that give the number of rows and number of bricks in a row. This

is undesirable (you might forget to change them back). Instead, we can use the fact

that this is an application and give the application some values when it starts out.

When you run your application (again, assuming that it is in a folder called

breakout) try the command

python breakout 3 2

fix_bricks in __main__.py,

which writes the values into the "constants" controller.BRICKS_IN_ROW and

controller.BRICK_ROWS respectively. (It also updates BRICK_WIDTH

appropriately.)

The result is that (once you have setting up of bricks working correctly)

your game will put up your

customized number of rows and bricks per row, again, with the purpose of making it easier to test

your win/lose code.

Create (and Animate) the Paddle

Next you need to create the black paddle. You will need to reference the paddle often, so

again we have provided you with a hidden instance variable called _paddle. As with the bricks,

create an object of type GRectangle and add it

to the view. You should do this immediately after creating the bricks (either in that

helper function, or as part of on_touch_down).

There are some advantages to making a subclass of GRectangle to represent the paddle;

you can offload some of the setup (e.g. setting the color and size) to your paddle class,

and you can distinguish the paddle from other GRectangle objects using

isinstance. However, this design decision is up to you; you may prefer just

to instantiate GRectangle directly.

The real challenge with the paddle is making it move. In order to do that, you will need

to make use of the on_touch_… methods in Breakout:

on_touch_down, on_touch_up, and on_touch_move.

To move the paddle, you will take advantage of the fact that each of the on_touch

methods has a parameter touch which stores a

MotionEvent

object. This object has attributes x and y which store the location

of the mouse or touch event.

The way to get the paddle to follow the mouse is simple: whenever you get an event telling

you that the mouse (or touch point) has moved, change the horizontal position of the paddle

(that is, the GRectangle instance you added to the view) so that it is centered

at the event's x coordinate.

Important Considerations

You need to ensure that the

paddle stays completely on the board even if the touch moves off the board. Our code for this

is 3 lines long; it uses the functions min and max.

Your implementation of the on_touch methods should only allow the paddle

to be moved when the game is ongoing. That is, the state should either be STATE_PAUSED

or STATE_ACTIVE.

Don't forget that once you have set the bricks and paddle up, you should switch the state to STATE_PAUSED. And whenever you are in state STATE_PAUSED, you should tell the user, via display of a message, that they need to click to serve the ball. In one of the figures above, you can see our message, “3 turns left; click to serve”.

Try to complete this part by April 29.

Create a Ball and Make it Bounce

You are now past the "setup" phase and into the "play" phase of the game. In this phase,

a ball is created and moves and bounces appropriately. For the most part, a ball is just

an instance of GEllipse. However, since the

ball moves it does not just have a position. It also has a velocity (vx,vy). Since

velocity is a property of the ball, it makes sense for these to be attributes of the ball object.

There

are no such attributes in GEllipse, so we have to subclass GEllipse

to add them. When you make a subclass of GEllipse, you inherit all its methods

and attributes

(remember to call the GEllipse initializer from your initializer),

including its position, size, color, etc.

Keep in mind that the pos attribute inherited by this class specifies

the bottom-left corner, and not the center of the ball.

You should initialize the attributes vx, vy in the initializer

for Ball (which you should write). Initially, the ball should head downward, and

we'd like a moderate speed. The ball's position is measured in pixels, and the velocity

measures the distance the ball moves in one call

to update, which happens once per animation frame, or 60 times per second.

So the velocity is measured in

pixels per frame, and a value of -5.0

(5 pixels per frame in the downward direction) makes a reasonable choice.

(Setting the velocity to too large a positive or negative value

will make the ball “teleport”

through bricks and/or the paddle, given the way we do collision detection in this

assignment.)

So you should use a starting velocity of -5.0 for vy. The game would be boring

if every ball took the same course, so you should choose component vx randomly.

Do this with the module random, which has functions for generating random numbers.

In particular, you should initialize the vx attribute as follows:

self.vx = random.uniform(1.0,5.0)

self.vx = self.vx * random.choice([-1, 1])

vx to be a random float in the range 1.0 to 5.0 (inclusive).

The second line multiplies it by -1 half the time (i.e., making it negative).

Serve the Ball

Serving the ball is as simple as adding it to the view (and storing it in the provided instance

variable _ball).

In addition, when you serve the ball, you should set the state to STATE_ACTIVE,

indicating that the game is ongoing and there is a ball in play.

Move the Ball

To move the ball, you must implement the last major method, update. This method

is essentially the body of a loop which is called 60 times a second. The loop runs "forever"—as long as the application is still running.

Each time update is called, it should move the ball a bit and change the

ball direction if it hits a wall. Do not worry about collisions with the bricks or

paddle. For now, the ball will travel through them like a ghost. You will deal

with collisions in the next task.

The update method moves the ball one step at a time. To move the ball

one step, simply add the ball's velocity components to the ball's corresponding position

coordinates. You might even want to add a method to the Ball class that

does this for you. Once you have moved the ball one step, do the following:

Suppose the ball is going up. Then, if any part of the ball has a y-coordinate

greater than or equal to GAME_HEIGHT, the ball has reached the top and its

direction has to be changed so that it goes down. Do this by setting vy to

-vy. Check the other three sides of the game board in the same fashion.

When you have finished this, the ball will bounce around the playing board forever—until you stop it.

The only tricky part is checking that any part of the ball has reached (or gone over)

one of the sides. For example, to see whether the ball has gone over the right edge,

you need to test whether the right side of the ball is over that edge; on the other

hand, to see whether the ball has gone over the left edge, you must test the left

side of the ball. See the attributes in GObject

for clues on how to do this.

Complete this part by April 30.

Check for Collisions

Now comes the interesting part. In order to make Breakout into a real game, you have to be

able to tell when the ball collides with another object in the window. As scientists often

do, we make a simplifying assumption and then relax the assumption later. Suppose the ball

were a single point (x,y) rather than a circle. Then, for any GObject

gobj, the method call

gobj.collide_point(x,y)

True if the point is inside of the object and False if

it is not.

However, the ball is not a single point. It occupies physical area, so it may collide with something on the screen even though its center does not. The easiest thing to do — which is typical of the simplifying assumptions made in real computer games — is to check a few carefully chosen points on the outside of the ball and see whether any of those points has collided with anything. As soon as you find something at one of those points (other than the ball, of course) you can declare that the ball has collided with that object.

One of the easiest ways to come up with these "carefully chosen points" is to treat everything

in the game as rectangles. A

One of the easiest ways to come up with these "carefully chosen points" is to treat everything

in the game as rectangles. A GEllipse is defined in terms of its bounding rectangle

(i.e., the rectangle in which it is inscribed). Therefore the lower left corner of the ball is

at the point (x,y) and the other corners are at the locations shown in the diagram

to the right (d is the diameter of the ball).

These points are outside of the ball, but they are close enough to make it appear that a

collision has occurred.

You should write a hidden helper method (for what class?) called

_getCollidingObject with the following specification:

def _getCollidingObject(self):

"""Returns: GObject that has collided with the ball

This method checks the four corners of the ball, one at a

time. If one of these points collides with either the paddle

or a brick, it stops the checking immediately and returns the

object involved in the collision. It returns None if no

collision occurred."""

In writing this method, depending on how you have set things up, you may find the instance

variables _bricks and _paddle

of Breakout to be useful.

You now need to modify the update method of Breakout,

discussed above.

After moving the ball, call _getCollidingObject to check for a collision. If

the ball going up collides with the paddle, do not do anything. If the ball going down

collides with the paddle, negate the vertical direction of the ball. If the ball (going

in either vertical direction) collides with a brick, remove the brick from the board and

negate the vertical direction. Remember our comments above about

removing bricks.

Try to finish this part by May 2.

Finish the Game

You now have a (mostly) working game. However, there are two minor details left for you to take care before you can say that the game is truly finished.

Player Lives

You need to take care of the case that the ball hits the bottom wall. Right now, the ball just bounces off this wall like all the others, which makes the game really easy. But hitting the bottom is supposed to mean that the ball is gone. In a single game, the player should get three balls before losing.

If the player can have another ball, the update method should put a message

on the board somewhere (as you did on the welcome screen) telling the player that another

ball is coming. At this point the state should again be STATE_PAUSED,

indicating that the game is in session but no ball is currently moving (otherwise,

update will continue to try to move a ball that does not exist).

Just as at the start, when the user clicks you will serve up a new ball, switch the state back

to STATE_ACTIVE,

and continue the game as normal.

Winning or Losing

Eventually the game will end. Each time the ball drops off the bottom of the screen, you

need to check if there are any tries left. If not, the game is over. Additionally, as

part of the update method, you need to check whether the bricks are all gone.

As you have been storing the active bricks in _bricks, an easy way to do this

is to check the length of this list. When the list is empty, the game ends and the player

has won.

When the game ends, and the player has either won or lost, you should put up one last

message. Use a GLabel to put up a congratulatory (or admonishing) message.

Finally, you should change the state one last time to indicate that the game is over.

That is what the state STATE_COMPLETE is for.

Finish this part by the due date, Saturday, May 4th at 11:59 pm.

Extending the Game

Optionally, you may like to extend the game and try to make

it more fun. In doing this, you might find yourself reorganizing a lot of the code above. You may

add new methods, or change any of the five main methods above. You may add new classes; for example,

you may decide to make Brick a subclass of GRectangle (as you did with

Ball and GEllipse) and so that the various bricks can hold extra information

(e.g. power-ups). You can even change any of the constants.

All of this is acceptable. Now that you have proved that you can get the code working, you are free to change it as you see fit. However, we highly suggest that you save a copy of the basic game in a separate folder before you start to make major changes. That way you have something to revert to if things go seriously awry when implementing your extensions. Also, we suggest that you make sure to comment your code well in order to keep track of where you are in the coding process.

Extensions are not mandatory, but they do affect grading. Add more and we will be much more lenient with our grading than if you implemented the bare minimum (i.e., everything up to this point). However, note that a submission that does not have good specifications for the helper methods or invariants for the new fields will not be looked at kindly under any circumstances. Also, no amount of fancy extras will result in a score above the maximum—the fastest and easiest way to a perfect score on this assignment is with an exemplary implementation of the basics.

Possible Extensions

Here are some possible ways to extend the game, though you should not be constrained by any of them. Make the game you want to make. We will reward originality more than we will reward quantity. While this is a fairly simple game, the design space is wide open with possibilities.

Improve user control over bounces

The game gets rather boring if the only thing the player has to do is hit the ball. Let the player control the ball by hitting it with different parts of the paddle. For example, suppose the ball is coming down toward the right (or left). If it hits the left (or right) 1/4 of the paddle, the ball goes back the way it came (both vx and vy are negated).

Implement "Try Again"

Let the player play as many games as they want. The player could click the mouse button

to start a new game. You will need to change the method on_touch_down to

implement this functionality.

Implement sound effects

It is an easy extension to add appropriate sounds for game events. We have provided several audio files in A7.zip. You are not restricted by those; you can easily find lots more (but it is a violation of the Academic Integrity Policy to use copyrighted material in your assignment).

To load an audio file, you simply create a Sound object

as follows:

bounceSound = Sound('bounce.wav')

bounceSound.play(). The sound might get monotonous after a while,

so make the sounds vary, and figure out a way to let the user turn sound off (and on).

Read the online specification to see how to use Sound objects. In particular, if you want to play the same sound multiple times simultaneously (such as when you hit two bricks simultaneously), you will need two different Sound objects for the same sound file.

Add a kicker

The arcade version of Breakout lures you in by starting off slowly. But as soon as you think you are getting the hang of things, the ball speeds up, making life more exciting. Implement this in some fashion, perhaps by doubling the horizontal velocity of the ball on the seventh time it hits the paddle.

Keep score

Design some way to score the player's performance. This could be as simple as the number of bricks destroyed. However, you may want to make the bricks in the higher rows more valuable.

You should display the score at all times using a GLabel object. Where

you display it is up to you (except do not keep the player from seeing the balls, paddle,

or bricks). Remember that, to change the score, you do not need to remove and re-add

the GLabel. Simply change the text attribute in your

GLabel object.

Use your imagination

What else have you always wanted a game like this to do? At some point your game might stop being like Breakout and be more like Arkanoid. Do not go too wild with the power-ups, however. We much prefer a few innovations that greatly improve the play.

Completing the Assignment

Before submitting anything, test your program to see that it works. Play for a while and make sure that as many parts of it as you can check are working. If you think everything is working, try this: just before the ball is going to pass the paddle level, move the paddle quickly so that the paddle collides with the ball rather than vice-versa. Does everything still work, or does your ball seem to get "glued" to the paddle? If you get this error, try to understand why it occurs and how you might fix it.

When you are done, re-read the specifications of all your methods and functions (including those we stubbed in for you), and be sure that your specifications are clear and that your functions follow their specifications. If you implemented extensions, make sure your documentation makes it very clear what your extensions are.

As part of this assignment, we expect you to follow our style guidelines.

- There are no tabs in the file, only spaces.

- Classes are separated from each other by two blank lines.

- Methods are separated from each other by a single blank line.

- Class contents are ordered as follows: class variables (if any), initializer, operators (if any), methods.

- Lines are short enough that horizontal scrolling is not necessary (about 80 chars is long enough).

- The specifications for all of the methods and variables are complete.

- Method specifications are immediately after the method header and indented.

Finally, at the top of your module controller.py add a brief description of

any extensions. Just add it as a comment (use single line comments; this is not part

of your specification). Tell us what you were trying to do.

Turning it In

Upload the

file controller.py

to CMS by

the due date: Saturday, May 4th at 11:59 pm.

If you have extra files to submit (e.g. custom sound or art files), put all your

files in a zip file called everything.zip and submit this instead.

We need to be able to play your game, and if anything is missing, we cannot play it.