%%html

<style>

.emph4780 {

font-weight: bold;

color: navy;

}

.red4780 {

font-weight: bold;

color: red;

}

.diagram4780 {

display: block;

margin-left: auto;

margin-right: auto;

}

.diagram4780 img {

width: 80%;

padding: 16px;

}

#myimg1 {

display: inline;

margin-top: 0px;

}

#myimg2 {

display: inline;

margin-top: 0px;

}

</style>

import numpy as np

import sys

import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.io import loadmat

import time

from pylab import *

from helperfunctions import knn_demo_1, knn_demo_2, knn_demo_3, curse_demo_1, curse_demo_2, curse_demo_3

from matplotlib.animation import FuncAnimation

%matplotlib notebook

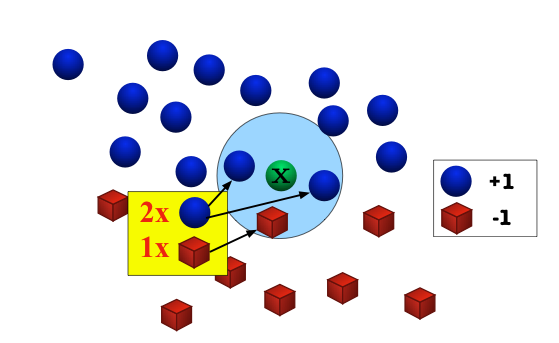

Assumption: Nearby inputs have similar outputs.

Hypothesis: Given a test input $x$, output the most common label among its $k$ most-similar training inputs.

What should we do in case of a tie?

Most common distance: the Euclidean distance $$\operatorname{dist}(u,v) = \| u - v \|_2 = \sqrt{ \sum_{i=1}^d (u_i - v_i)^2 }$$

Also popular: the taxicab norm (a.k.a. Manhattan norm) $$\operatorname{dist}(u,v) = \| u - v \|_1 = \sum_{i=1}^d |u_i - v_i|$$

For parameter $p \ge 1$

$$\operatorname{dist}(u,v) = \| u - v \|_p = \left( \sum_{i=1}^d |u_i - v_i|^p \right)^{1/p}$$Generalizes many other norms, including the popular $\ell_2$ (Euclidean), $\ell_1$ (taxicab), and $\ell_{\infty}$ (max norm).

%matplotlib notebook

knn_demo_1()

%matplotlib notebook

knn_demo_2()

Click on the images above, to cycle through the test images.

knn_demo_3()

interactive(children=(IntSlider(value=1, description='k', max=19, min=1, step=2), Output()), _dom_classes=('wi…

The Bayes Optimal Classifier is the hypothesis

$$h_{\operatorname{opt}}(x) = \arg \max_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} \; \mathcal{P}(y | x) = \arg \max_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} \; \mathcal{P}(x, y).$$

Conditional probability of damage $x$ conditioned on label $y$.

| Damage | Wolf (1d6+1) | Werewolf (2d4) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1/6 | 1/16 |

| 3 | 1/6 | 1/8 |

| 4 | 1/6 | 3/16 |

| 5 | 1/6 | 1/4 |

| 6 | 1/6 | 3/16 |

| 7 | 1/6 | 1/8 |

| 8 | 0 | 1/16 |

Joint density: $\mathcal{P}(x,y) = \mathcal{P}(x | y) \mathcal{P}(y) = \mathcal{P}(x | y) \cdot \frac{1}{2}$

| Damage | Wolf (1d6+1) | Werewolf (2d4) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1/12 | 1/32 |

| 3 | 1/12 | 1/16 |

| 4 | 1/12 | 3/32 |

| 5 | 1/12 | 1/8 |

| 6 | 1/12 | 3/32 |

| 7 | 1/12 | 1/16 |

| 8 | 0 | 1/32 |

Always guess the label with the highest probability.

| Damage | Wolf (1d6+1) | Werewolf (2d4) | Bayes Optimal Classifier Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1/12 | 1/32 | Wolf |

| 3 | 1/12 | 1/16 | Wolf |

| 4 | 1/12 | 3/32 | Werewolf |

| 5 | 1/12 | 1/8 | Werewolf |

| 6 | 1/12 | 3/32 | Werewolf |

| 7 | 1/12 | 1/16 | Wolf |

| 8 | 0 | 1/32 | Werewolf |

Does this being "optimal" mean we get it right all the time?

We get it wrong when the true label disagrees with our prediction.

| Damage | Wolf (1d6+1) | Werewolf (2d4) | Bayes Optimal Classifier Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1/12 | 1/32 | Wolf |

| 3 | 1/12 | 1/16 | Wolf |

| 4 | 1/12 | 3/32 | Werewolf |

| 5 | 1/12 | 1/8 | Werewolf |

| 6 | 1/12 | 3/32 | Werewolf |

| 7 | 1/12 | 1/16 | Wolf |

| 8 | 0 | 1/32 | Werewolf |

$\operatorname{error} = \frac{1}{32} + \frac{1}{16} + \frac{1}{12} + \frac{1}{12} + \frac{1}{12} + \frac{1}{16} + 0 = \frac{13}{32} \approx 41\%.$

Another important baseline is the Best Constant Predictor.

$$h(x) = \arg \max_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} \; \mathcal{P}(y).$$We can bound the error of 1-NN relative to the Bayes Optimal Classifier.

Suppose that $(\mathcal{X}, \operatorname{dist})$ is a separable metric space.

Let $x_{\text{test}}$ and $x_1, x_2, \ldots$ be independent identically distributed random variables over $\mathcal{X}$. Then almost surely (i.e. with probability $1$)

$$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \; \arg \min_{x \in \{x_1, \ldots, x_n\}} \operatorname{dist}(x, x_{\text{test}}) = x_{\text{test}}.$$Consider the case where any ball of radius $r$ centered around $x_{\text{test}}$ has positive probability.

Then, no matter now close the current nearest neighbor is to $x_{\text{test}}$, every time we draw a fresh sample $x_i$ from the source distribution, with some probability it will be closer than the nearest neighbor currently in the distribution.

This implies that the distance diminishes to $0$ with probability $1$.

Consider the case where there is some ball of radius $r$ centered around $x_{\text{test}}$ that has probability zero in the source distribution.

But this must happen with zero probability in the random selection of $x_{\text{test}}$.

Why? Let $Z$ be the set of all points in $\mathcal{X}$ that have the property that they are the center of some ball with zero probability. Then because $\mathcal{X}$ is separable, we can cover $Z$ with the union of a countable number of balls with zero probability. So $Z$ itself must have zero probability.

You defintely don't need to know this topology stuff for CS4/5780, but I think it's good to mention it so you have some intuition about when NN might fail on exotic spaces.

Let $x_{\text{test}}$ denote a test point randomly drawn from $\mathcal{P}$. Let $\hat x_n$ (also a random variable) denote the nearest neighbor to $x_{\text{test}}$ in an independent training dataset of size $n$.

The expected error of the 1-NN classifier is $$ \operatorname{error}_{\text{1-NN}} = \mathbf{E}\left[ \sum_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} \mathcal{P}(y | \hat x_n) \left(1 - \mathcal{P}(y | x_{\text{test}})\right) \right]. $$ This is the sum over all labels $y$ of the probability that the prediction will be $y$ but the true label will not be $y$.

Taking the limit as $n$ approaches infinity, the expected error is \begin{align*} \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \; \operatorname{error}_{\text{1-NN}} &= \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \; \mathbf{E}\left[ \sum_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} \mathcal{P}(y | \hat x_n) \left(1 - \mathcal{P}(y | x_{\text{test}})\right) \right] \\&= \mathbf{E}\left[ \sum_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} \mathcal{P}(y | x_{\text{test}})) \left(1 - \mathcal{P}(y | x_{\text{test}})\right) \right] \end{align*}

Let $\hat y$ denote the prediction of the Bayes Optimal Classifier on $x_{\text{test}}$. \begin{align*} \lim{n \rightarrow \infty} \; \operatorname{error}{\text{1-NN}} &= \mathbf{E}\left[ \mathcal{P}(\hat y | x{\text{test}}) \left(1 - \mathcal{P}(\hat y | x{\text{test}})\right) \right] \&\hspace{2em}+ \mathbf{E}\left[ \sum{y \ne \hat y} \mathcal{P}(y | x{\text{test}})) \left(1 - \mathcal{P}(y | x{\text{test}})\right) \right] \&\le \mathbf{E}\left[ 1 \cdot \left( 1 - \mathcal{P}(\hat y | x{\text{test}}) \right) \right] + \mathbf{E}\left[ \sum{y \ne \hat y} 1 \cdot \mathcal{P}(y | x{\text{test}})) \right] \&=

2 \mathbf{E}\left[ 1 - \mathcal{P}(\hat y | x_{\text{test}})\right]

=

2 \operatorname{error}_{\text{Bayes}}.

\end{align*}

k-NN works by reasoning about how close together points are.

In high dimensional space, points drawn from a distribution tend not to be close together.

First, let's look at some random points and a line in the unit square.

fig = plt.figure(); X=np.random.rand(50,2);

plot(X[:,0],X[:,1],'b.'); plot([0,1],[0.5,0.5],'r-'); axis('square'); axis((0,1,0,1));

Consider what happens when we move to three dimensions. The points move further away from each other but stay equally close to the red hyperplane.

(fig,animate) = curse_demo_1()

ani = FuncAnimation(fig, animate,arange(1,100,1),interval=10);

curse_demo_2()

curse_demo_3()

The pairwise distance between two points in a unit cube (or sphere, or from a unit Gaussian) increases with dimension.

In comparison, the distance to a hyperplane does not increase.

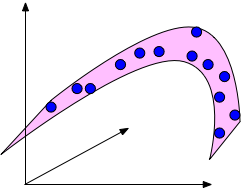

If the data lies in a low-dimensional submanifold, then we can still use low-dimensional methods even in higher dimensions.

Please finish the prelim exam (placement quiz)!

First homework is out tonight!