So far we've been talking about performance as though all steps in the evaluation model are equally expensive. This turns out not to be even approximately true; they can differ by two orders of magnitude or more. Asymptotically, it doesn't matter, because there is an upper bound on how long each step takes. But in practice, a 100-fold slowdown can matter if it's affecting the performance-critical part of the program. To write fast programs, we sometimes need to understand how the performance of the underlying computer hardware affects the performance of the programming language, and to design our programs accordingly.

Computers have a memory, which can be abstractly thought of as a big array of

ints, or more precisely, of 32-bit words. The indices into

this array are called addresses. Depending on the processor, addresses may be

either 32 bits long (allowing up to 4 gigabytes to be addressed) or 64 bits,

allowing a memory four billion times larger. The operations supported by the

memory are reading and writing, analogous to Array.sub and

Array.update:

module type MEMORY = sig type address (* Returns: read(addr) is the current contents of memory at addr. *) val read: address -> int (* Effects: write(addr, x) changes memory at addr to contain x. *) val write: address * int -> unit end

All of the rich features and types of a higher level language are

implemented on top of this simple abstraction. For example, every

variable in the program has, when it is in scope, a location in memory

assigned to it. (Actually the compiler tries to put as many variables

as possible into registers, which are much faster than

memory, but we can think of these as just other memory locations for

the purpose of this discussion.) For example, if we declare

let x: int = 2, then at run time there is a memory location

for x, which we can represent as a box containing the number 2:

Since a variable box can only hold 32 bits, many values cannot fit in

the location of their variable. Therefore the language implementation puts such values elsewhere

in memory. For example, a tuple let x = (2,3,4) would be represented

as three consecutive memory locations, which we can draw as boxes.

The memory location (box) for x would contain the address of the first of these

memory locations. We can think of this address as an arrow pointing from

the box for x to the first box of the tuple. Therefore we refer to this address

as a pointer. Since the actual memory addresses don't usually

matter, we can draw diagrams of how memory is being used that omit the

addresses and just show the pointers.

A tuple type is an example of a boxed type: its values are too large to fit inside the memory location of a variable, and so need their own memory locations, or boxes. Unboxed types in OCaml include the basic types such as int, char, bool, real, nil, and NONE. Boxed types include tuples, records, datatypes, list nodes, arrays, refs, strings, and functions.

Every time we have a variable name with a boxed

type, it means that there to access that value, the processor must use a

pointer address to get to the data. Following pointers is called an

indirection.

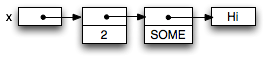

For example, if we declare a variable let x = (2, Some "Hi"),

three indirections are needed to get to the characters of the string "Hi":

The reason we care about whether there are pointers or not is that indirections can be very expensive. To understand why, we need to look at how computer memory works more carefully.

The memory of a computer is made of a bunch of big arrays etched into various chips. Each array has a large number of row and column lines that the memory chip can independently activate. At the intersection of each row and column line, there is a a bit of storage implemented using one or more transistors.

To read bits out of a row of memory, each transistor on the row has to pump enough electrons onto or off of its column line to allow sensing logic on the column to detect whether that bit was 0 or 1. All else equal, bigger memories are slower because the transistors are smaller relative to the column line they have to activate. As a result, computer memory has gotten slower and slower relative to the speed of processing (e.g., adding two numbers). Adding two numbers takes one cycle (or even less on multiple-issue machines such as the x86 family). A typical computer memory these days takes about 30ns to deliver requested data. This sounds pretty fast, but you have to keep in mind that a 4GHz processor is doing a new instruction every 0.25ns. Thus, the processor will have to wait more than 100 cycles every time the memory is needed to deliver data. Quite a bit of computation can be done in the time it takes to fetch one number from memory.

To deal with the relative slowdown of computer memory, computer architects have introduced caches, which are smaller, faster memories that sit between the CPU and the main memory. A cache keeps track of the contents of memory locations recently requested by the processor. If the processor asks for one of these locations, the cache gives the answer instead. Because the cache is much smaller than main memory (hundreds of kilobytes instead of tens or hundreds of megabytes), it can be made to deliver requests much faster than main memory: in tens of cycles rather than hundreds. In fact, one level of cache isn't enough. Typically there are two or three levels of cache, each smaller and faster than the next one out. The primary (L1) cache is the fastest cache, usually right on the processor chip and able to serve memory requests in one–three cycles. The secondary (L2) cache is larger and slower. Modern processors have at least primary and secondary caches on the processsor chip, often tertiary caches as well. There may be more levels of caching (L3, L4) on separate chip.

For example, the Itanium 2 processor from Intel has three levels of cache right on the chip, with increasing response times (measured in processor cycles) and increasing cache size. The result is that almost all memory requests can be satisfied without going to main memory.

These numbers are just a rule of thumb, because different processors are configured differently. The Pentium 4 has no on-chip L3 cache; the Core Duo has no L3 cache but has a much larger L2 cache (2MB). Because caches don't affect the instruction set of the processor, architects have a lot of flexibility to change the cache design as a processor family evolves.

Having caches only helps if when the processor needs to get some data, it is already in the cache. Thus, the first time the processor access the memory, it must wait for the data to arrive. On subsequent reads from the same location, there is a good chance that the cache will be able to serve the memory request without involving main memory. Of course, since the cache is much smaller than the main memory, it can't store all of main memory. The cache is constantly throwing out information about memory locations in order to make space for new data. The processor only gets speedup from the cache if the data fetched from memory is still in the cache when it is needed again. When the cache has the data that is needed by the processor, it is called a cache hit. If not, it is a cache miss. The ratio of the number of hits to misses is called the cache hit ratio.

Because memory is so much slower than the processor, the cache hit ratio is critical to overall performance. For example, if a cache miss is a hundred times slower than a cache hit, then a cache miss ratio of 1% means that half the time is spent on cache misses. Of course, the real situation is more complex, because secondary and tertiary caches often handle misses in the primary cache.

The cache records cached memory locations in units of cache lines containing multiple words of memory. A typical cache line might contain 4–32 words of memory. On a cache miss, the cache line is filled from main memory. So a series of memory reads to nearby memory locations are likely to mostly hit in the cache. When there is a cache miss, a whole sequence of memory words is requested from main memory at once. This works well because memory chips are designed to make reading a whole series of contiguous locations cheap.

Therefore, caches improve performance when memory accesses exhibit locality: accesses are clustered in time and space, so that reads from memory tends to request the same locations repeatedly, or even memory locations near previous requests. Caches are designed to work well with computations that exhibit locality; they will have a high cache hit ratio.

How does caching affect us as programmers? We would like to write code that has good locality to get the best performance. This has implications for many of the data structures we have looked at, which have varying locality characteristics.

Arrays are implemented as a sequence of consecutive memory locations. Therefore, if the indices used in successive array operations have locality, the corresponding memory addresses will also exhibit locality. There is a big difference between accessing an array sequentially and accessing it randomly, because sequential accesses will produce a lot of cache hits, and random accesses will produce mostly misses. So arrays will give better performance if there is index locality.

Lists have a lot of pointers. Short lists will fit into cache, but long lists won't. So storing large sets in lists tends to result in a lot of cache misses.

Trees have a lot of indirections, which can cause cache misses. On the other hand, the top few levels of the tree are likely to fit into the cache, and because they will be visited often, they will tend to be in the cache. Cache misses will tend to happen at the less frequently visited nodes lower in the tree.

One nice property of trees is that they preserve locality. Keys that are close to each other will tend to share most of the path from the root to their respective nodes. Further, an in-order tree traversal will access tree nodes with good locality. So trees are especially effective when they are used to store sets or maps where accesses to elements/keys exhibit good locality.

Hash tables are arrays, but a good hash function destroys much locality by design. Accessing the same element repeatedly will bring the appropriate hash bucket into cache. But accesses to keys that are near each other in any ordering on keys will result in memory accesses with no locality. If keys have a lot of locality, a tree data structure may be faster even though it is asymptotically slower!

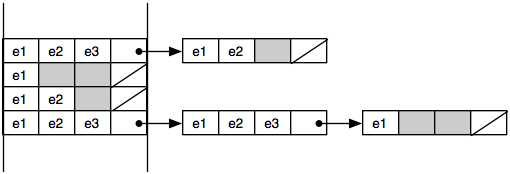

Lists use the cache ineffectively. Accessing a list node causes extra information on the cache line to be pulled into cache, possibly pushing out useful data as well. For best performance, cache lines should be used fully. Often data structures can be tweaked to make this happen. For example, with lists we might put multiple elements into each node. The representation of a bucket set is then a linked list where each node in the linked list contains several elements (and a chaining pointer) and takes up an entire cache line. Thus, we go from a linked list that looks like the one on top to the one on the bottom:

Doing this kind of performance optimization can be tricky in a language like Ocaml where the language is working hard to hide these kind of low-level representation choices from you. A rule of thumb, however, is that OCaml records and tuples are stored nearby in memory. So this kind of memory layout can be implemented to some degree in OCaml, e.g.:

type 'a onelist = Null | Cons of 'a * 'a onelist type 'a chunklist = NullChunk | Chunk of 'a * 'a * 'a * 'a * int * 'a chunklist let cons x (y: 'a chunklist) = match y with Chunk(_,_,_,a,1,tail) -> Chunk(x,x,x,a,2,tail) | Chunk(_,_,b,a,2,tail) -> Chunk(x,x,b,a,3,tail) | Chunk(_,c,b,a,3,tail) -> Chunk(x,c,b,a,4,tail) | (Chunk(_,_,_,_,_,_) | NullChunk) -> Chunk(x,x,x,x,1,y) let rec find (l:int chunklist) (x:int) : bool = match l with NullChunk -> false | Chunk(a,b,c,d,n,t) -> (a=x || b=x || c=x || d=x || find t x)

The idea is that a chunk stores four elements and a counter that keeps track of the number of element fields (1-4) that are in use. It turns out that scanning down a linked list implemented in this way is about 10 percent faster than scanning down a simple linked list (at least on a 2009 laptop). In a language like C or C++, programmers can control memory layout better and can reap much greater performance benefits by taking locality into account. The ability to carefully control how information is stored in memory is perhaps the best feature of these languages.

Since hash tables use linked lists, they can typically be improved by the same chunking optimization. To avoid chasing the initial pointer from the bucket array to the linked list, we inline some number of entries in each array cell, and make the linked list be chunked as well. This can give substantial speedup but does require some tuning of the various parameters. Ideally each array element should take occupy one cache line on the appropriate cache level. Best performance is obtained at a higher load factor than with a regular linked list. Other pointer-rich data structures can be similarly chunked to improve memory performance.

In OCaml programs (and in most other programming languages), it is possible to

create

let x = [[1; 2; 3]; [4]] in let y = [2] :: List.tl x in y

Here the variable x is bound to a list of two

elements, each of which is itself a list. Then the

variable y is bound to a list that drops the first

element of x and adds a different first element and the

function returns this new list. Since x is never used

again that first list is inaccessible, or garbage.

Any boxed value created by OCaml can become garbage. This includes tuples, records, strings, arrays, lists and function closures as well as most user-defined data types.

Most garbage collectors are based on the idea of reclaiming whole blocks that

are no longer

Looking at memory more abstractly, we see that the memory heap is simply a directed graph in which the nodes are blocks of memory and the edges are the pointers between these blocks. So reachability can be computed as a graph traversal.

There are two basic strategies for dealing with garbage: manual storage management by the programmer and automatic garbage collection built into the language run-time system. Language constructs for manual storage management are provided by languages like C and C++. There is a way for the programmer to explicitly allocate blocks of memory when needed and to deallocate (or "free") them when they become garbage. Languages like Java and OCaml provide automatic garbage collection: the system automatically identifies blocks of memory that can never be used again by the program and reclaims their space for later use.

Automatic garbage collection offers the advantage that the programmer does not have to worry about when to deallocate a given block of memory. In languages like C, the need to manage memory explicitly complicates any code that allocates data on the heap and is a significant burden on the programmer, not to mention a major source of bugs:

In practice, programmers manage explicit allocation and deallocation by keeping track of what piece of code "owns" each pointer in the system. That piece of code is responsible for deallocating the pointer later. The tracking of pointer ownership shows up in the specifications of code that manipulates pointers, complicating specification, use, and implementation of the abstraction.

Automatic garbage collection helps modular programming, because two modules can share a value without having to agree on which module is responsible for deallocating it. The details of how boxed values will be managed does not pollute the interfaces in the system.

Programs written in OCaml and Java typically generate garbage at a high rate, so it is important to have an effective way to collect the garbage. The following properties are desirable in a garbage collector:

Fortunately, modern garbage collectors provide all of these important properties. We will not have time for a complete survey of modern garbage collection techniques, but we can look at some simple garbage collectors.

To compute reachability accurately, the garbage collector needs to be able to

identify pointers; that is, the edges in the graph.

Since a word of memory cells is just a sequence of bits, how

can the garbage collector tell apart a pointer from an integer? One simple

strategy is to reserve a bit in every word to indicate whether the value in that

word is a pointer or not. This

A different solution is to have the compiler record information that the garbage collector can query at run time to find out the types of the various locations on the stack. Given the types of stack locations, the successive pointers can be followed from these roots and the types used at every step to determine where the pointers are. This approach avoids the need for tag bits but is substantially more complicated because the garbage collector and the compiler become more tightly coupled.

Finally, it is possible to build a garbage collector that works even if you

can't tell apart pointers and integers. The idea is that if the collector

encounters something that looks like it might be a pointer, it treats it as if

it is one, and the memory block it points to is treated as reachable. Memory is

considered unreachable only if there is nothing that looks like it might be a

pointer to it. This kind of collector is called a

Mark-and-sweep proceeds in two phases: a

Marking for reachability is essentially a graph traversal; it can be

implemented as either a depth-first or a breadth-first traversal. One problem with a straightforward

implementation of marking is that graph traversal takes O(n) space where

n is

the number of nodes. However, this is not as bad as the graph traversal we considered earlier, one needs only a single bit per node in the graph if we modify the nodes to explicitly mark them as having been visited in the search. Nonetheless, if garbage collection is being performed because the system

is low on memory, there may not be enough added space to do the marking

traversal itself. A simple solution is to always make sure there is enough space

to do the traversal. A cleverer solution is based on the observation that there

is O(n) space available already in the objects being traversed. It is possible

to record the extra state needed during a depth-first traversal on top of the

pointers being traversed. This trick is known as

In the sweep phase, all unmarked blocks are deallocated. This phase requires the ability to find all the allocated blocks in the memory heap, which is possible with a little more bookkeeping information per each block.

When should the garbage collector be invoked? An obvious choice is to do it

whenever the process runs out of memory. However, this may create an excessively

long pause for garbage collection. Also, it is likely that memory is almost

completely full of garbage when garbage collection is invoked. This will reduce

overall performance and may also be unfair to other processes that happen to be

running on the same computer. Typically, garbage collectors are invoked

periodically, perhaps after a fixed number of allocation requests are made, or a

number of allocation requests that is proportional to the amount of non-garbage

(

One problem with mark-and-sweep is that it can take a long time—it has to

scan through the entire memory heap. While it is going on, the program is

usually stopped. Thus, garbage collection can cause long pauses in the

computation. This can be awkward if, for example, one is relying on the program

to, say, help pilot an airplane. To address this problem there are

Collecting garbage is nice, but the space that it creates may be scattered among many small blocks of memory. This external fragmentation may prevent the space from being used effectively. A compacting (or copying) collector is one that tries to move the blocks of allocated memory together, compacting them so that there is no unused space between them. Compacting collectors tend to cause caches to become more effective, improving run-time performance after collection.

Compacting collectors are difficult to implement because they change the locations of the objects in the heap. This means that all pointers to moved objects must also be updated. This extra work can be expensive in time and storage.

Some compacting collectors work by using an

A final technique for automatic garbage collection that is occasionally used

is

There are a few problems with this conceptually simple solution:

Applications for the Apple iPhone are written in Objective C, but there is no garbage collector available for the iPhone at present. Memory is managed manually by the programmer using a built-in reference counting scheme.

Generational garbage collection separates the memory heap into two or more

After an allocated object survives some number of minor garbage collection cycles, it is promoted to the tenured generation so that minor collections stop spending time trying to collect it.

Generational collectors introduce one new source of overhead. Suppose a program

mutates a tenured object to point to an untenured object. Then the

untenured object is reachable from the tenured set and should not be collected.

The pointers from the tenured to the new generation are called the

The goal of a garbage collector is to automatically discover and reclaim fragments of memory that will no longer be used by the computation. As mentioned, most objects are short-lived; a typical program allocates lots of little objects that are only in use for a short period of time, then can be recycled.

Most garbage collectors are based on the idea of reclaiming whole objects

that are no longer reachable from a

At an abstract level, a

For example, suppose memory looks like this, where the colored boxes represent different objects, and the thin black box in the middle represents the half-way point in memory.

| Obj 1 | Obj 2 | Obj 3 | Obj 4 | Obj 5 |

At this point, we've filled up half of memory, so we initiate a collection. Old space is on the left and new space on the right. Suppose further that only the red and light-blue boxes (objects 2 and 4) are reachable from the stack. After copying and compacting, we would have a picture like this:

| Obj 1 | Obj 2 | Obj 3 | Obj 4 | Obj 5 | Obj 2' | Obj 4' |

Notice that we copied the live data (the red and light-blue objects) into new space, but left the unreachable data in the first half. Now we can "throw away" the first half of memory (this doesn't really require any work):

| Obj 2 | Obj 4 |

After copying the data into new space, we restart the computation where it left off. The computation continues allocating objects, but this time allocates them in the other half of memory (i.e., new space). The fact that we compacted the data makes it easy for the interpreter to allocate objects, because it has a large, contiguous hunk of free memory. So, for instance, we might allocate a few more objects:

| Obj 2 | Obj 4 | Obj 6 | Obj 7 | Obj 8 |

When the new space fills up and we are ready to do another collection, we flip our notions of new and old. Now old space is on the right and new space on the left. Suppose now that the light-blue (Obj 4), yellow (Obj 6), and grey (Obj 8) boxes are the reachable live objects. We copy them into the other half of memory and compact them, throwing away the old data:

| Obj 4 | Obj 6 | Obj 8 |

What happens if we do a copy but there's no extra space left over? Typically, the garbage collector will ask the operating system for more memory. If the OS says that there's no more available (virtual) memory, then the collector throws up its hands and terminates the whole program.

We have described a fairly simple take on garbage collection. There are many different algorithms, such as mark and sweep, generational, incremental, mostly-copying, etc. Often, a good implementation will combine many of these techniques to achieve good performance. You can learn about these techniques in a number of places—perhaps the best place to start is the Online GC FAQ.

OCaml uses a hybrid generational garbage collector that uses two separate

heaps, one for small objects (the

The Java 5 garbage collector is also a generational collector with three

generations. In the two youngest generations, a copying collector is used,

but the third and oldest generation is managed by a