Assignment 4: Formula evaluation

Programming languages give us as programmers the ability to evaluate mathematical expressions like a calculator, including expressions that involve variables.

The language’s compiler translates the formula into instructions that a computer’s CPU can execute.

But what if we want our program’s users to be able to type in their own expressions at runtime and have them be evaluated?

Their formula will be user input (a String), not source code, so we’ll need our program to evaluate it step-by-step with the help of appropriate data structures.

As an application, let’s once again consider spreadsheets.

Some cells contain plain text or numbers, but other cells may specify a formula that should be used to compute its value, taking as input the values of other cells.

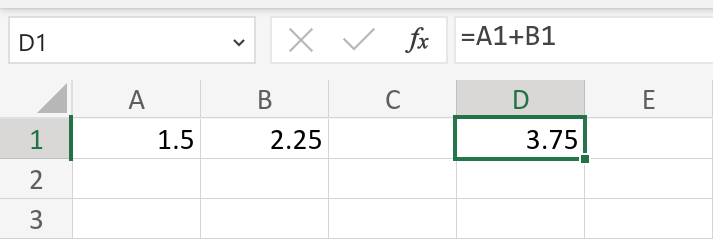

For example, in Microsoft Excel, the formula =A1+B1 means that the cell’s value should be the sum of the values in row 1, columns A & B (see figure).

In this assignment, you will write an application that evaluates postfix formulas in spreadsheets saved in CSV format. Along the way you will develop an interactive calculator to help build intuition for the data structures involved. This project involves a lot of Java classes; some of them will be given to you (in which case you must study their specifications as a client), while others you will develop from scratch. As usual, you will write JUnit test cases for all of your code, annotated with human-readable assertions of specifications.

Learning Objectives

- Leverage subtype polymorphism to represent expression trees containing multiple kinds of nodes.

- Process tree data structures recursively.

- Report and respond to failed operations using exceptions.

- Write tests for methods expected to throw exceptions using lambda expressions.

- Use classes from a third-party library.

Recommended schedule

Start early. This is a big assignment! Office hours and consulting hours are significantly quieter shortly after an assignment is released than closer to the deadline. We recommend spreading your work over at least 5 days. Here is an example of what that schedule could be:

- Day 1: Read this handout and open the project in IntelliJ. Confirm that the test suites compile and run.

Part I—Test and implementeval()andopCount()for allExpressionclasses. Write “stubs” for all otherExpressionmethods so that your code compiles and your tests can run. - Day 2: Part I continued—Test and implement

infixString()andpostfixString()for allExpressionclasses. Then test and implementequals()(which will come in handy for future tests). - Day 3: Part II—Test and implement

RpnParser, then perform further testing by usingRpnCalcto interact with your expression trees. - Day 4: Part III—Return to your

Expressionclasses and test and implementdependencies()andoptimize(). UseRpnCalcto see this functionality in action. - Day 5: Part IV—Implement

CsvEvaluator. Test it both with the provided unit tests and with the provided CSV files. Try creating and evaluating a few spreadsheets of your own.

Note that this schedule does not include the challenge extensions. If you plan on tackling these, be sure to leave an extra couple of days at the end of your schedule.

Collaboration policy

On this assignment you may work together with one partner. Having a partner is not needed to complete the assignment: it is definitely do-able by one person. Nonetheless, working with another person is useful because it gives you a chance to bounce ideas off each other and to get their help with fixing faults in your shared code. If you do intend to work with a partner, you must review the syllabus policies pertaining to partners under “programming assignments” and “academic integrity.”

Partnerships must be declared by forming a group on CMSX before starting work. The deadline to form a CMS partnership is Thursday, October 19. After that, CMSX will not allow you to form new partnerships on your own. You may still email your section TA (CCing your partner) to form a group late, but a 5 point penalty will be applied. This is to make sure you are working with your partner on the entire assignment, as required by the syllabus, rather than joining forces part way through.

As before, you may talk with others besides your partner to discuss Java syntax, debugging tips, or navigating the IntelliJ IDE, but you should refrain from discussing algorithms that might be used to solve the problems, and you must never show your in-progress or completed code to another student who is not your partner. Consulting hours are the best way to get individualized assistance at the source code level.

Frequently asked questions

Note: This is a brand-new assignment for Fall 2023, and there are a lot of interactions to keep track of. Some tasks may be a little unclear at first, but we will try to post fixes and clarifications as these are reported on Ed.

Additionally, this assignment includes some “challenge extensions” that are worth very few points but will provide a lot of additional practice for students who choose to tackle them. Do not feel discouraged if you don’t have time to try these challenges—you can still earn an ‘A’ grade without attempting them at all. If you do attempt them, course staff will only be able to provide limited debugging assistance.

If needed, there will be a pinned post on Ed where we will collect any clarifications for this assignment. Please review it before asking a new question in case your concern has already been addressed. You should also review the FAQ before submitting to see whether there are any new ideas that might help you improve your solution.

Note that the student handbook has been updated to clarify some of the requirements that apply to all assignments in this course. Please ensure that your submission complies with these to avoid deductions during grading.

Assignment overview

For this assignment you will be creating three Java classes from scratch (representing polymorphic expression tree nodes) and completing two applications: an interactive calculator and a spreadsheet formula evaluator.

Make sure to open the “a4” folder as a project in IntelliJ following the procedure we’ve recommended all semester (this is extra important for this assignment, as it depends on a third-party library in the “lib” folder). Here is a brief tour of what you’ll find inside your project:

- Expression.java

- An interface that must be implemented by each kind of node that might appear in an expression tree. (do not modify)

- Constant.java

- A class implementing

Expressionthat represents plain numbers. (do not modify)

You will need to create Variable.java, Application.java, and Operation.java to represent other things that could occur in a mathematical expression. Use the implementation ofConstantas a guide. - tests/…/ExpressionTest.java

- A JUnit test suite consisting of several classes (one for each kind of expression node).

The tests forConstanthave been written for you. Required tests for the other classes have been declared and described with@DisplayName(), but you will need to implement them. - Operation.java, UnaryFunction.java

- Classes representing algebraic operators and mathematical functions; they will appear as fields in your

OperationandApplicationclasses. (do not modify)

Skim these (or their JavaDocs) to learn their public methods, as well as to see which operators and functions are conveniently available as public fields. But don’t worry about understanding how they are implemented. - VarTable.java, MapVarTable.java

- An interface and an implementing class for storing values that have been assigned to expression variables. Passed to

Expressionobjects when evaluating them. (do not modify)

Skim these to learn the interface, as well as some utility functions that are convenient when testing. The implementation illustrates the use of the Map ADT (which we’ll get to later), but it is otherwise uninteresting. - RpnParser.java

- Defines a static method for parsing expressions.

A rough outline of the implementation is given, but you must complete it. - tests/…/RpnParserTest.java

- A test suite for

RpnParser. (modify, but do not submit)

Some tests are provided, but you will want more.

- Token.java

- An abstract class and several subclasses representing different tokens that may appear in an expression string. (do not modify)

Skim the subclasses and their methods and read the specification forparse(). You will use values returned byparse()when implementingRpnParser. - RpnCalc.java

- An interactive calculator program (has a

main()method). - UnboundVariableException.java, IncompleteRpnException.java, UndefinedFunctionException.java

- Custom exception classes used in this project. Note how we can define custom messages and properties. (do not modify)

- CsvEvaluator.java

- A program that reads spreadsheets in CSV format, evaluates their formulas, and writes the results in CSV format (has a

main()method).

You will need to implement two utility functions in this class. - tests/…/CsvEvaluatorTest.java

- A test suite for

CsvEvaluator. (modify, but do not submit)

Some tests are provided; you may want more. - lib/commons-csv-1.10.0.jar

- A third-party library for reading and writing CSV files.

We will describe its usage below, but you are also welcome to skim its JavaDocs. Do not attempt to read anything in this file (it only contains compiled bytecode). - calc-commands.txt, calc-commands-out.txt

- Sample input file that can be passed to

RpnCalc, along with the expected output (includes challenge extensions). - pizza.csv, pizza-out.csv

- A sample spreadsheet containing formulas that

CsvEvaluatorcan evaluate, along with the expected results. - reflection.txt

- Template for submitter metadata and reflection questions

Whew! Your programs are getting bigger! Fortunately, you only need to worry about submitting 4 of these files (plus 3 new ones you will create).

Note that achieving reasonable coverage of the expression classes requires a lot of test cases. But each one only needs a couple lines of code, and we have provided English descriptions of the cases that you need.

Part I: Expression nodes

Background

Expression trees

As discussed in lecture 14, a tree is a natural data structure for representing mathematical expressions, since operands and function arguments are themselves subexpressions. Consider the expression . The operands to the multiplication operator are the constant and the subexpression . And the whole subexpression serves as the first operand to the addition operator. These hierarchical relationships form a tree as shown in the figure, which each node containing either a constant, a variable, or an operator.

Expressions are evaluated recursively: an operator node recursively evaluates its left operand, then its right operand, and then combines those returned values to produce its result.

An operator always has two children (its left and right operands), but in this assignment we will also support function nodes, like sin() and cos(), that have a single child (their argument subexpression).

To review mathematical expressions and their representation as trees, see the following textbook sections:

- Segment 5.5 (Using a Stack to Process Algebraic Expressions), focusing on 5.17–5.18

- Chapter 24, 24.22–24.24 (Expression Trees)

Reverse Polish notation (RPN)

We are used to writing mathematical expressions in “infix” notation, like 2*(y - 1) + 3.

However, this notation requires knowing the precedence of each operator (e.g., multiplication/division before addition/subtraction), and parentheses are often required to achieve the desired order of operations.

Parsing such expressions in software is, consequently, a little tricky.

But there is another way to write expressions that never requires parentheses, corresponding to a postorder traversal of the corresponding expression tree.

This is called “postfix notation,” a.k.a. “reverse Polish notation” (RPN).

As an example, the previous expression would be written in RPN as 2 y 1 - * 3 +.

For this assignment, all formulas typed into your calculator or saved in spreadsheets will be in reverse Polish notation.

Here are some correspondences between our infix and RPN notations:

| Infix | Postfix (RPN) |

|---|---|

(1 - 2) |

1 2 - |

((y + 1) / (2 * z)) |

y 1 + 2 z * / |

(2 * sin((pi / 2))) |

2 pi 2 / sin() * |

Note that, to eliminate any possibility of ambiguity, every binary operation is enclosed in parentheses in our infix notation.

Our Expression interface

Our expression trees will be composed of polymorphic nodes implementing the Expression interface.

This means that each node could have a different class, each one specializing Expression in a particular way (i.e., constant numbers vs. binary operators).

For example, the expression would be represented by the following tree, where “C” indicates a Constant node, “V” indicates a Variable node, “A” indicates an Application node, and “O” indicates an Operation node:

Here is a class diagram showing the methods required by Expression and the fields of the concrete classes that you’ll be writing:

Expressions can be evaluated, they can count how many operations are required to evaluate them, and they can write themselves in infix or postfix notation. Read the specifications in “Expression.java” for the specifics.

The Constant class has been written for you.

It represents a single number, stored in its value field.

Your task

Define public classes Variable, Application, and Operation implementing the Expression interface in new corresponding “.java” files.

Start by creating “stubs” for each of the required methods (IntelliJ can do this for you; see below).

Declare the fields that will represent each class’s state according to the class diagram above, then define constructors to initialize those fields.

You can choose whether to implement all the methods in one class before moving on to the next one, or whether to implement one method at a time across all of the classes. We recommend the latter, as it will enable you to test each operation on arbitrary expressions as you go.

Here is a brief overview of these three classes.

These descriptions should be enough for you to write specialized specifications for eval(), opCount(), infixString(), postfixString(), and equals() in each class.

The remaining operations will be discussed later.

Variable nodes

These represent a named variable (like ) in an expression; their state is simply the variable’s name.

Variables are useful because they allow us to write down an expression without yet knowing the values of all of the terms.

For example, in our spreadsheet formulas, variables with names like “B1” will refer to values in other cells of the spreadsheet.

To evaluate expressions containing variables, a client must pass in a VarTable containing the values of those variables.

Like constants, variable nodes are leaf nodes and have no children.

When evaluated, they return the value of their variable (if it exists in the VarTable), or else they throw an UnboundVariableException.

We do not consider this lookup to be an “operation” as counted by opCount().

When a variable is written as a string, a variable is simply represented by its name, regardless of notation (infix vs. postfix).

Since variable nodes are leaves, two of them are equal if they represent the same variable name.

Application nodes

These represent the application of a function to an argument; the argument can be any non-empty subexpression.

For example, the expression expresses the application of the function to the subexpression .

The argument is stored as a single child Expression node.

The function to call is an instance of our UnaryFunction class, which can be evaluated on a numeric argument by calling its apply() method.

UnaryFunction can also report its name so we know how to identify the function in a string.

To evaluate an Application node, it should evaluate its argument child, then apply its function to that value and return the result.

Calling its function counts as one “operation”.

In infix notation, an Application is represented by the name of its function, followed by the infix representation of its argument, enclosed in parentheses.

For example, the expression above would be written as "sin((y / 2))" (note the double parentheses—one pair for the function application, and one pair for the Operation argument, to be discussed next).

In postfix notation, an Application is represented by its argument’s postfix string, followed by the function name with a "()" suffix (this is to distinguish functions from variables).

Two Application nodes are equal if their functions and arguments are equal.

Operation nodes

These represent the binary operators common in arithmetic: addition (+), subtraction (-), multiplication (*), division (/), and exponentiation (^).

Their operands are stored as two child Expression nodes, distinguishing between left and right (since subtraction, division, and exponentiation are not commutative).

The operator is an instance of our Operator class, which can be evaluated on numeric operands by calling its operate() method.

Operator can also report its symbol so we know how to identify it in a string.

To evaluate an Operation node, it should evaluate both of its operand children, then combine those value with its operator and return the result.

This counts as one “operation”.

In infix notation, an Operation is always enclosed in parentheses, and its operands are separated from its operator symbol by spaces.

What we would write mathematically as should be expressed as the string "(((2 * y) + 1) ^ 3)".

To express an Operation in postfix notation, simply perform a postorder traversal, as discussed in lecture for binary trees.

The same expression in postfix notation would be "2 y * 1 + 3 ^".

Two Operation nodes are equal if their operator and operands are equal.

Note: you should not need to do any dynamic type queries (i.e., instanceof, getClass(), casting) when implementing the behavior of the various expression nodes (other than in equals(), where our usual template is fine).

Nor should you need to write any loops.

Rely on recursion and subtype polymorphism and trust your child nodes to do the right thing.

Testing expressions

“ExpressionTest.java” declares nearly 50 unit tests for the various Expression classes.

About half of the tests have been implemented for you, while you are responsible for implementing the remaining ones.

As usual, we strongly recommend implementing (or uncommenting) the tests related to the behavior you are about to implement.

Writing (or reading) the test case will clarify the function’s specification for you, and seeing the case change from “fail” to “pass” provides a reward when your method implementation is on the right track.

And if a test doesn’t turn green, you know exactly which code must be at fault.

These unit tests demonstrate better testing style than ones on previous assignments.

Each case is annotated with a @DisplayName() that describes the behavior being tested.

The description gives the context, identifies the operation being performed, and specifies the expected result (this loosely follows a template known as “given…when…then…").

It is hopefully clear how each case relates to the specifications of a class’s methods; occasionally these descriptions may even help clarify a dense specification.

For each case that says fail(); // TODO, you are responsible for replacing this stub with a test implementation that meets the criteria described by the @DisplayName().

You are encouraged to copy-paste portions of other tests to speed up this process as long as the result is consistent with the test description.

Some tests have already been implemented but have been commented out.

This is because we did not specify the constructor signatures for your Expression classes.

You must uncomment each of these cases and adjust the constructor invocations (if necessary) so that the tests run.

Despite the relatively large number of tests in this suite, it probably still does not provide 100% line coverage of your classes (though hopefully it covers at least 90%). Furthermore, it does not come close to testing all possible combinations of node types, operators, functions, and variable names. But writing clear specifications at the interface level, then testing that each component meets those specifications individually, is still critical for avoiding bugs when composing software modules in arbitrary ways like this.

Testing exceptions

Since some of the methods promise to throw an exception under certain conditions, you should include tests that check whether an exception is thrown as specified.

The JUnit function assertThrows() is the right tool for the job, but it works a little differently than other JUnit assertions.

You must specify the expected exception’s Class object, and you must defer execution of the exception-throwing code using an anonymous function.

Let’s take testEvalUnbound() in VariableExpressionTest as an example.

When eval() is called on a Variable expression expr, we expect it to throw an UnboundVariableException if the variable’s name is not in the provided VarTable argument.

This behavior is tested using the following code:

assertThrows(UnboundVariableException.class, () -> expr.eval(MapVarTable.empty()));

We’ll come back to anonymous functions in more detail later in the course, but for now you can use them in this idiomatic way by just putting () -> in front of expressions whose evaluation needs to be deferred.

Part II: Parsing RPN expressions

As you likely concluded from your testing, assembling expression trees from individual nodes is tedious.

We need a way to parse a postfix expression string, provided by a user, and return the corresponding expression tree (this is basically the inverse of the postfixString() methods you implemented earlier).

This is the job of RpnParser.parse().

Implementing this parser is the most important part of the assignment.

Since we didn’t dictate the order of constructor arguments for your Expression classes, the only way our autograder will be able to create expression nodes is by parsing expression strings using your RpnParser.

It will also probably be the longest method you write for this assignment.

Given an expression in RPN, you build the expression tree from the bottom up using the following procedure:

- Initialize a Stack of expression nodes.

- For each token in the expression (left-to-right):

- If the token is a number or a variable name, push a corresponding leaf node onto the stack.

- If the token is an operator or a function name, pop the appropriate number of operands/arguments off of the stack, construct a new interior node with the operation and arguments, and push the new node onto the stack.

- Assuming the expression is valid, there will be one node left on the stack. This is the root of the expression tree.

Playing with an RPN calculator can help build your intuition for this procedure.

In RpnParser.parse(), we start you off with a few key elements: an empty stack of Expression nodes and an iteration over Tokens.

The tokens are created by splitting the expression string at whitespace, then determining whether each substring is a number, an operator, a function call (ending in "()"), or a variable name (any other string).

Each token will therefore be one of the following subclasses of Token (the Token. prefix just indicates that they were defined as nested classes in the same file):

Token.NumberToken.Operator(note: this is not the same class asOperator)Token.FunctionToken.Variable

As described by the TODO, you should query the dynamic type of each token yielded by the iteration (using instanceof), then take the appropriate action for each kind.

If you ever need to pop more expressions off the stack than are available, you should throw IncompleteRpnException; likewise if, at the end of the procedure, there is not exactly one Expression remaining.

Note that each subclass of Token defines some useful behavior, accessible via appropriate casting.

For example, a Token.Operator can give you its corresponding Operator object via opValue().

Functions, however, must be looked up from the funcDefs argument provided by the client (this is to support user-defined functions, one of the challenge extensions).

Implement your parser, then test it against the cases in RpnParserTest.

Note that this testing is deliberately incomplete.

Heed the advice in the comments add additional test cases to ensure that your parser is working as expected.

There are plenty of examples of postfix expressions in this handout that you can use.

Part III: Calculator functionality

Once your parser is implemented, you can interact with your expressions using the RpnCalc calculator app.

This calculator has already been implemented (except for a few advanced functions left as challenges), so go ahead and run it and type help to see the commands that are available.

The calculator remembers the last expression that was entered, so if you do not provide a new expression with each command, it will reuse the old one (the square brackets around [<expr>] in the help message indicate that the argument is optional).

Type eval 2 1 1 0 + + + to evaluate . Type infix to print the expression in infix notation. Type opcount to count the number of operations needed to evaluate it. To exercise variables and functions, try set pi 3.1415926535897932, then eval pi 2 / sin().

The file “calc-commands.txt” contains another sequence of calculator commands.

To run them all at once, you can pass the filename as a program argument to RpnCalc.

However, it will crash when trying to run the deps and optimize commands if you still have stubs in your expression classes.

Let’s fix that.

Variable dependencies

If a formula gets very long, it might be handy to know all of the variables it depends on. Since the same variable may appear in multiple subexpressions, a Set of variable names is the appropriate ADT to represent this information (so duplicates are not repeated).

Implement the dependencies() method in all of your Expression classes.

A Variable node depends on itself.

All other nodes interior nodes depend on the union of their children’s dependencies (this is all you need to know to document the refined specs for each class).

Your implementation must be recursive and, as before, should not do any runtime type checking on Expressions.

You are allowed to use Set, HashSet, and/or TreeSet from java.util to implement this.

Be aware that the convenient Set.of() methods produce unmodifiable sets, so if you need to add more elements, you’ll need to construct a new set of a concrete class that you can add to.

Optimization

If a formula contains a lot of operations, it can be expensive to evaluate it over and over again (as you might do when graphing a function, for example). But if a subexpression only depends on constants or variables whose values are known and fixed, then the value of that subexpression won’t change with repeat evaluations. Therefore, we can replace the subtree representing that subexpression with a constant node to avoid having to recompute the operations. This is an optimization known as constant folding.

Implement the optimize() method in all of your Expression classes.

A Variable can only be optimized if it has an assigned value in the provided variable table, in which case it optimizes to a Constant; otherwise, it optimizes to itself.

An Application or Operation node can be fully optimized to a Constant if its children can all be evaluated to yield a number.

But even if a child depends on an unbound variable, the parent node can still be partially optimized by creating a new copy whose children are replaced with their optimized forms.

These rules should be sufficient for you to document the refined specs for each class.

If you have any doubts about the expected behavior, take a look at the test cases.

As an example, optimizing the expression when is assigned the value yields the simpler expression :

Assignment metadata

You’ve made great progress!

At this point, you can fill in some of the fields in “reflection.txt”.

Enter your name and NetID (both partners if working in a group), then answer the verification questions using RpnCalc.

Part IV: Spreadsheet evaluator

Now that you have a working RPN expression evaluator, let’s put it to work evaluating spreadsheet formulas.

The CsvEvaluator application should read the rows and columns of a spreadsheet saved in a CSV file and copy them in CSV format to System.out.

But when it encounters a cell whose value starts with an equals sign, =, it should parse the remainder of that cell’s value as an RPN formula, evaluate it, and print that value instead.

If the formula cannot be evaluated for any reason, it should be replaced by #N/A in the output.

A spreadsheet formula may refer to values in other cells by using their column–row coordinates as variables in the expression.

For example, the formula in the Excel screenshot at the start of this handout would be written as =A1 B1 +, where A1 refers to the cell in the first column (A) of the first row, while B1 refers to the cell in the second column (B) of the first row.

Formulas may refer to cells containing either numbers or other formulas, but for simplicity, a formula may only refer to cells on previous rows or cells on the same row but in previous columns (lifting this restriction requires computing a “topological ordering” of formulas, which you will learn how to do later in the course).

Here is an example of the program’s input and output, shown as tables (the row and column headers would not be included in the CSV output):

Input

| A | B | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | x | 1.5 |

| 2 | y | =B1 4 * 1 + |

| 3 | z | =B1 B2 * |

| 4 | w | =A1 |

Output

| A | B | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | x | 1.5 |

| 2 | y | 7.0 |

| 3 | z | 10.5 |

| 4 | w | #N/A |

The main() method of CsvEvaluator has been written for you.

Your task is to implement evaluateCsv() according to its specifications.

But in order to do so, you’ll first want a helper function to convert between column numbers and column letters.

Column labels

Traditionally, spreadsheet columns are labeled by letters, rather than numbers. The first column is labeled ‘A’, the second column is labeled ‘B’, etc. If more than 26 columns are used, a second letter is added: ‘AA’ is 27, ‘AB’ is 28, and so on. To convert a column position into its label, we need to represent the number in this base-26 numeral system. But because there is no letter corresponding to 0, the process is a little bit different.

Expressing integers in different bases is a classic (exam) problem with a recursive solution. First, the number is divided by the base , yielding an integer quotient and a remainder . These obey the relationship , subject to . The ones digit of the representation is then the remainder , and the rest of the digits are simply the base- representation of the quotient, . The base case is when the quotient is 0, in which case no more digits should be written to the left.

But the column labeling scheme is what’s known as a “bijective numeral system”, which do not use a 0 digit (the number 0 itself is written as the empty string). The algorithm is very similar to that for positional notation, except that the “quotient” is defined slightly differently: it is the largest integer that, when multiplied by the base , is strictly less than (recall that a normal quotient is the largest integer that, when multiplied by , is less than or equal to ). The relationship between the quotient and remainder is the same as before, meaning that now .

With this in mind, implement colToLetters() to recursively convert column positions to labels.

Note that this will require converting integers to characters; thankfully, Latin letters in alphabetical order correspond to consecutive integers in Unicode.

Therefore, to find, e.g., the 5th letter in the alphabet (which is 4 letters after ‘A’), one can write (char)('A' + 4).

Working with CSV files

As mentioned in A3, writing a robust parser for CSV files requires a lot of attention to detail in order to accommodate strings that contain commas or newlines. Rather than reinventing the wheel, we should take advantage of solutions that other programmers have already written and tested. To do so, this assignment includes a third-party dependency, a free and open-source class library named “Apache Commons CSV”.

CsvEvaluator has already done the work of setting up this library and creating a CSVParser to read the user’s input file and a CSVPrinter to print a CSV file to the console.

Your solution will need to iterate over the rows and cells of the input (each row is an instance of CSVRecord) and print rows of cells to the printer.

While you may use any of the methods provided by these classes, the following ones are sufficient to get the job done:

CSVParser.iterator(): Iterator<CSVRecord>- You probably won’t call this directly, but its existence means you can use an enhanced

for-loop to iterate over each row (“record”) in a CSV file. CSVRecord.iterator(): Iterator<String>- Again, no need to call this directly, but its existence means you can use an enhanced

for-loop to iterate over each cell’s value in a row (“record”). CSVPrinter.print(String)- Call this to append a new cell to the current row being written.

CSVPrinter.println()- Call this to finish the current row being written and move on to the next row.

Note that, unlike in A3, there is no need to read the whole file into a list-of-lists or equivalent data structure. Since formulas can only depend on previous cells, you can write each cell as soon as you have read it. This approach is known as “online” processing.

Testing

The included CsvEvaluatorTest provides reasonably good coverage of both colToLetters() and evaluateCsv().

It also comments on cases that are known to not be covered by these tests.

It is up to you to determine which of these situations might pose a risk to your implementation and to add additional tests as appropriate.

You do not need to submit these tests, but that does not make them any less essential to confidently delivering a working solution.

For an end-to-end test of the whole application, try running it with the program argument “pizza.csv”. The output should match the contents in “pizza-out.csv”.

Part V: Challenge extensions

The last few points of the assignment are reserved for challenge tasks. These require a significant amount of effort for relatively few points and are intended as additional exercise for students who complete the rest of the assignment ahead of schedule. It is okay to attempt none of the challenge tasks; they are not included in the recommended schedule. If you do not want to attempt a challenge, there is no need to upload the corresponding file.

Alternative VarTable implementation (3 points)

You have used the MapVarTable class when writing test cases for expression nodes and when implementing the calculator and spreadsheet evaluator.

As its name suggests, it is implemented using a Java HashMap.

But the methods in Expression accept any implementation of the VarTable interface, meaning you can use an alternative class instead.

Implement a class named TreeVarTable that implements the VarTable interface using a binary search tree data structure (see Chapter 26).

All related code must go in the file “TreeVarTable.java” and must be appropriately documented.

You must implement your own tree from scratch (using Java’s TreeMap does not qualify, nor may you copy-paste the textbook or lecture demo implementations).

Be sure to test your class thoroughly with a JUnit test suite (which you do not need to submit).

You may use your TreeVarTable class instead of MapVarTable throughout the rest of the assignment (as a form of end-to-end testing), but we do not necessarily recommend submitting this, as any bugs in your TreeVarTable would then count against the code that depends on it.

Additional calculator functionality (2 points)

Implement the following additional features in RpnCalc, replacing their corresponding TODOs:

-

tabulate <var> <lo> <hi> <n> [<expr>]: Evaluate the current expression (expr if provided, otherwise the previously set expression) n times, varying the value of variable var between lo and hi. Print a line for each evaluation containing the current value of var followed by the value of the expression.Example—tabulate the expression for in the range of 0 to 4:

> tabulate x 0 4 5 x 2 ^ 0.0 0.0 1.0 1.0 2.0 4.0 3.0 9.0 4.0 16.0After executing this command, var should have the value hi.

-

def <name> <var> [<expr>]: Define a new function named name that will evaluate the current expression (expr if provided, otherwise the previously set expression) with variable var set to the function’s argument. This function can then be used in future expressions. Unlike variables, functions may not be redefined (attempting to do so is a user error and should be reported as such). Additionally, an expression used to define a function may not depend on any variables other than var (thedefcommand handler should check this).Example—define a function

sqr()that squares its argument, then use it in an expression:> def sqr x x 2 ^ > eval 3 sqr() 9

If the user makes an error in invoking one of these commands, your command handler should print a helpful error message to System.err and return (it should not propagate any exceptions).

Note that Scanner’s exceptions are unchecked, so you’ll need to study its documentation to know what to catch.

Submission

Return to “reflection.txt”, estimate the amount of time you spent on this assignment, and answer the reflection question. Then submit the following files:

- Variable.java

- Application.java

- Operation.java

- ExpressionTest.java

- RpnParser.java

- CsvEvaluator.java

- reflection.txt

- RpnCalc.java (optional—challenge extension)

- TreeVarTable.java (optional—challenge extension)

You hopefully wrote additional test cases for RpnParser and CsvEvaluator to improve your confidence in your solution, but those tests will not be submitted.

Smoketesting

The smoketester will check the following:

- Do each of your files compile “in isolation”? (that is, in the presence of reference implementations for all other classes; this means you cannot extend the public interface of any type)

- Your

Expressionclasses,ExpressionTestsuite, andRpnParserwill be compiled together, since constructors are not part of theExpressioninterface.

- Your

- Does your

ExpressionTestsuite pass when used to test your own implementations of theExpressionclasses? - Does your

RpnParserpass the test cases included in the release code? - What is the output of

RpnCalcwhen executing the commands in “calc-commands.txt”? - Does your

CsvEvaluatorpass the test cases included in the release code? - What is the output of

CsvEvaluatorwhen evaluating “pizza.csv”, and does it differ from “pizza-out.csv”?

Grading

When it comes time to grade your submission, the autograder will additionally check at least the following:

- Do your implementations of the

Expressionclasses, as created byRpnParser, pass our full test suite? - Do your

RpnParser,RpnCalc, andCsvEvaluatorpass our full test suites? - Do your challenge extensions pass our corresponding test suites?

As usual, manual grading will check for compliance with implementation constraints as well as adherence to good coding style.

Have fun!