Lecture 15:

Topological Sort

Consider a directed graph G=(V, E), consisting of a set of vertices V and a set of edges E (you can think of E as a subset of the Cartesian product V). Further, assume that if an edge e = (vi, vj) connects vertices vi and vj, respectively, then relationship R holds for vi and vj (vi R vi). For concreteness, we will identify the vertices of G with events. Also, we identify relationship R with the "must happen before" relation; we denote it by <.

Given this identification, we can now represent any set of events and "happened before" constraints with the help of a graph.

A graph that represents a consistent set of "happened before" constraints can not have cycles. We can easily prove this using reductio ad absurdum: Assume that the graph has a cycle, and vertex v0 is part of it. Consider edge (v0, v1), outgoing from vertex v0, which is part of the cycle at hand. Then the event denoted by vertex v0 must happen before the event denoted by vertex v1; v0 < v1. If the loop consists of vertices v0, v1, ..., vk, then we must have v0 < v1 < ... < vk. But the edge (vk, v0), which closes the cycle, implies that vk < v0. We get that v0 < v1 < ... < vk < v0. Thus the event denoted by v0 must occur before itself! This is clearly impossible; our assumption was wrong, the graph can not have cycles. A directed graph that does not contain cycles is called a directed acyclic graph, or DAG.

A linear ordering of the vertices of a DAG having the property that every vertex v in the respective ordering occurs before any other vertex to which it has edges is named topological sort. Every DAG admits a topological sort.

For the graphs representing "happened before" relations, a topological sort represents a linear ordering of events (vertices) so that an event is listed after all the events that must precede it, whether directly or indirectly.

In general, the topological sort is not unique. For example, if we have v0 < v1, and v2 < v3, any one of the orderings v1v2v3v4, v3v4v1v2, v1v3v2v4 is a topological sort. Note: We did not provide all topological sorts here; can you find another one?)

In the following, we will develop and implement a topological sort algorithm. As we will see, the topological sort algorithm is a direct extension of the depth-first search algorithm discussed in the preceding lecture.

Consider the graph that we have analyzed in the previous lecture. This is clearly not a DAG, because it has a cycle composed of nodes {4, 6, 5}. If we eliminated, say, edge (5, 4), then the graph would become a DAG. One of the topological sorts compatible with the resulting DAG is 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 5, 9, 8, 7. Note that node 7 can be inserted anywhere in the sequence - since it is isolated, its position is not constrained in any way.

Consider the graph that we have analyzed in the previous lecture. This is clearly not a DAG, because it has a cycle composed of nodes {4, 6, 5}. If we eliminated, say, edge (5, 4), then the graph would become a DAG. One of the topological sorts compatible with the resulting DAG is 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 5, 9, 8, 7. Note that node 7 can be inserted anywhere in the sequence - since it is isolated, its position is not constrained in any way.

For the topological sort algorithm we associate two nodes with each label: BEGIN and END. We also maintain a counter COUNT. Here is the algorithm:

Topological Sort Algorithm for DAGs

1.1. Set COUNT to 0.

For all vertices v in V, set BEGIN = END = 0.

1.2. Find a node v that has END = 0;

execute DFS(v). Repeat until no such nodes exist.

1.3. Order vertices so that their corresponding END

labels are in decreasing order.

DFS(v)

2.1. Increment COUNT by 1.

2.2. Set BEGIN(v) to COUNT.

2.3. For all nodes vi such that (v, vi) is an edge of G and BEGIN(vi) = 0,

perform DFS(vi).

2.4. Increment COUNT by 1.

2.5. Set END(v) to COUNT.

Note: In step (2.3) above, BEGIN(vi) must be 0 just before we start processing the node, not, for example, at the time we retrieve all nodes to which v has edges.

|

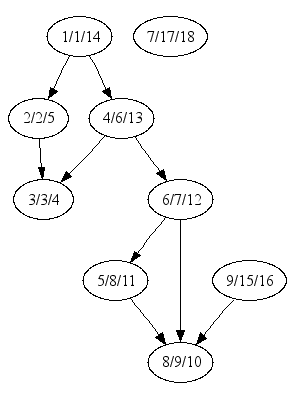

In the image at left we have represented the result of applying the topological sort algorithm to our graph (remember that we deleted the (5, 4) edge, so that the graph becomes a DAG). Node labels should be interpreted as node number/BEGIN label/END label. Based on the node labels, the resulting topological sort is 7, 9, 1, 4, 6, 5, 8, 2, 3.

Note that in this run of the topological sort algorithm we executed step (1.2) three times; the first time we selected node 1, the second time node 9, the third time node 7. This was quite "lucky" (actually manipulative), because it allowed up to sweep the majority of the nodes through a DFS search that started at node 1. What if we started at another - less propitious - node?

|

|

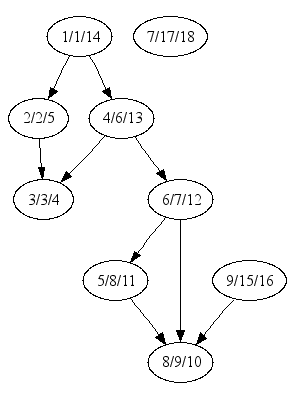

The graph at left at left shows the result of the topological sort algorithm for a different set of choices made in step (1.2). Can you establish number and the order of nodes chosen in this step?

The resulting topological sort is 1, 2, 9, 7, 4, 6, 3, 5, 8; it is significantly different from the sort that we got previously.

|

Our algorithm seems to work on DAGs, but what about graphs with cycles? We know that such graphs do not have topological sorts, but can we at least detect the existence of cycles? It turns out that we can, and we already have (better said: already generate) all the information needed for cycle detection.

Let us assume that our directed graph has (at least) one cycle. As we are exploring the graph, a generic path that does not include a cycle can not be distinguished from a portion of cycle, until we actually close the cycle. This implies that we can handle the problem of cycle detection by focusing on the last edge, say (vi, vj), which completes the cycle. We assume here that we can not see the graph from above - and programs can not - and that we did not process the graph previously to identify its cycles.

We can tell that edge (vi, vj) closes a (simple) cycle if the end-node of the edge (vj) has already been visited. Now, a node that has been visited before certainly has its BEGIN label set to a non-zero value, but what can we say about its END label?

It is easy to see that node vj must have been the first node in the cycle that has been explored (has its START label set); otherwise vj would not be the first node that was visited repeatedly in this cycle. The END label of node vj will only be set after the DFS algorithm fully explores all the paths outgoing from vj. But one of those paths is the one that lead to node vi, and then back to vj! This means that the END label of vj must still be 0.

We can now modify step (2.3) of the topological sort algorithm for DAGs so that it will work for general directed graphs:

2.3. For all nodes vi such that (v, vi) is an edge of G

(a) If BEGIN(vi) = 0, perform DFS(vi);

(b) If BEGIN(vi) > 0 and END(vi) = 0, then we have detected a cycle.

It our problem permits - or requires - it, we can always transform a directed graph into a DAG by dropping the edges identified in step (2.3)(b). Such edges are called back-edges - they go back to a node that has already been discovered (has a non-zero BEGIN label), but whose processing has not yet finished (its END label is 0).

Assuming that we discard all the back-edges and we finish executing the algorithm, then the relation BEGIN(vi) < BEGIN(vj) < END(vj) < END(vi) holds for each discarded back edge (vj, vi). Can you tell why? Does this relation hold for other pairs of nodes?

Is it possible for the topological sort algorithm to examine, in step (2.3) an edge whose end-node vi has already been fully explored (its END label is set to a non-zero value)? If yes, is this situation significant for the topological sort algorithm?

Let us now implement the topological sort algorithm for graphs represented using adjacency lists. Our implementation will use simple lists to record the values of the BEGIN and END labels as well. Rather than assigning an initial value of 0 to labels, we will only record values that have already defined to be non-zero.

type node = int

type graph = (node * node list) list

type labels = (node * int) list

fun topoSort(g: graph): node list =

let

fun findLabel(n: node, l: labels): int option =

case List.find (fn (n', _) => n' = n) l of

NONE => NONE

| SOME (_, l) => SOME l

fun findAdj(n: node): node list =

case List.find (fn (n', _) => n = n') g of

NONE => raise Fail "incomplete adjacency list"

| SOME (_, lst) => lst

fun dfs(count: int, toVisit: node list,

lbeg: labels, lend: labels): labels * labels * int =

case toVisit of

[] => (lbeg, lend, count)

| h::t =>

case (findLabel(h, lbeg), findLabel(h, lend)) of

(SOME _, NONE) => raise Fail ("back-edge detected; vertex " ^

(Int.toString h) ^ " is part of a cycle")

| (NONE, NONE) =>

let

val (lbeg, lend, count) = dfs(count + 1, findAdj h,

(h, count + 1)::lbeg, lend)

in

dfs(count + 1, t, lbeg, (h, count + 1)::lend)

end

| _ => dfs(count, t, lbeg, lend)

(* Go over the adjacency list; start a dfs search at every node *)

(* that has not already been processed. Skip processed nodes. *)

val (_, lend, _) = foldl (fn ((n, _), (lbeg, lend, count)) =>

case findLabel(n, lend) of

NONE => dfs(count, [n], lbeg, lend)

| SOME _ => (lbeg, lend, count))

([], [], 0)

g

in

(* Retrieve the node number from the list of end labels. *)

(* How do we know that we do not need to sort the resulting list? *)

map (fn (n, _) => n) lend

end

In the examples below g is the adjacency list representation of our favorite graph without the back-edge (5, 4), and g2 is the graph with the back-edge included:

- val g = [(1, [2, 4]), (2, [3]), (3, []),

= (4, [6]), (5, [8]), (6, [5, 8]),

= (7, []), (8, []), (9, [])];

val g =

[(1,[2,4]),(2,[3]),(3,[]),(4,[6]),(5,[8]),(6,[5,8]),(7,[]),(8,[]),(9,[])]

: (int * int list) list

-

-

- topoSort g;

val it = [9,7,1,4,6,5,8,2,3] : node list

-

-

- val g2 = [(1, [2, 4]), (2, [3]), (3, []),

= (4, [6]), (5, [4, 8]), (6, [5, 8]),

= (7, []), (8, []), (9, [])];

val g2 =

[(1,[2,4]),(2,[3]),(3,[]),(4,[6]),(5,[4,8]),(6,[5,8]),(7,[]),(8,[]),(9,[])]

: (int * int list) list

-

-

- topoSort g2;

uncaught exception Fail: back-edge detected; vertex 4 is part of a cycle

raised at: stdIn:621.33-622.79

-

We note that the above implementation is not particularly efficient (one reason for this is that searches in lists are slow).

Finally, we show below how the order in which the nodes are defined in the adjacency list influences the outcome of topological sort algorithm:

- val g = [(5, [8]), (3, []), (4, [6]),

= (6, [5, 8]), (7, []), (9, []),

= (1, [2, 4]), (2, [3]), (8, [])];

val g =

[(5,[8]),(3,[]),(4,[6]),(6,[5,8]),(7,[]),(9,[]),(1,[2,4]),(2,[3]),(8,[])]

: (int * int list) list

-

- topoSort g;

val it = [1,2,9,7,4,6,3,5,8] : node list

Are the actual label values in lbeg and lend important? If yes, why? If not, can you rewrite function topoSort to get rid of them?

Consider the graph that we have analyzed in the previous lecture. This is clearly not a DAG, because it has a cycle composed of nodes {4, 6, 5}. If we eliminated, say, edge (5, 4), then the graph would become a DAG. One of the topological sorts compatible with the resulting DAG is 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 5, 9, 8, 7. Note that node 7 can be inserted anywhere in the sequence - since it is isolated, its position is not constrained in any way.

Consider the graph that we have analyzed in the previous lecture. This is clearly not a DAG, because it has a cycle composed of nodes {4, 6, 5}. If we eliminated, say, edge (5, 4), then the graph would become a DAG. One of the topological sorts compatible with the resulting DAG is 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 5, 9, 8, 7. Note that node 7 can be inserted anywhere in the sequence - since it is isolated, its position is not constrained in any way.